Egg Man

*

‘Lazy Sunday afternoon

I’ve got no mind to worry…

Close my eyes and drift away’

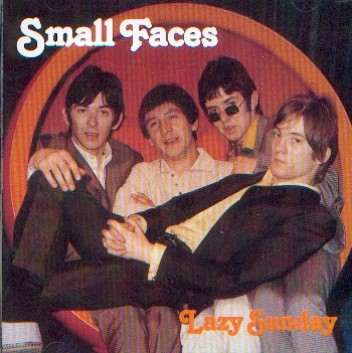

‘Lazy Sunday’ – Small Faces *

*

My parents first met in London during the late 1950s.

A successful meeting, I guess.

That’s why I’m here – and one reason why you’re reading this now.

London and I first met in the early 1960s. In the quiet and modest north London suburb of Muswell Hill.

‘Evil’ powers-that-be demolished the maternity clinic soon after.

With it, demolition must’ve also destroyed the Blue Plaque commemorating my arrival.

After this momentous event, my parents moved across north London to western Enfield, an even quieter ‘leafy’ suburb.

The street they hauled me to might as well have been called ‘Anywhere Gardens’.

During the mid-1960s, ‘Anywhere Gardens N21’ looked identical to hundreds of other suburban streets built between World War I and World War II – although this particular side road connected a local National Health Service hospital with a swathe of residential streets.

Regularly clipped grass verges, dotted with clover and dandelion, lined Anywhere Gardens. Cherry trees, festooned in Spring with radiant pink blossom, serenaded pedestrians and motorists with a garlanded guard of honour.

‘Spot’, a completely black retriever – chased cars down the street, barking madly.

Our neighbours – and friends – included ‘Uncle’ Bill, a taxi driver, and wife ‘Aunty’ Doris, a housecleaner – and their two boys, Colin and Mark, who kept rabbits and guinea pigs in their garden shed.

‘Uncle’ Jack, a clerk, and ‘Aunty’ Olive, a secretary from Yorkshire, lived next door. Terry, a glazier from Hackney, and his family, lived on the other side.

Hattie walked her two pet ferrets, tethered by string, up and down the road. Tony, her son – the ‘Egg Man’ – delivered eggs to local homes from the back of his car.

*

Home sweet home

Semi-detached houses and bungalows flanked the road on both sides of Anywhere Gardens.

All featured two larger bedrooms, a ‘box’ bedroom, separate living and dining rooms, a bathroom, and an inside toilet.

Each house or bungalow sported a small front and larger back garden with lawns and flowerbeds.

Car driveways led to sideways and garages roomy enough to shelter a Morris 1100 (above), a Ford Cortina, or even a Vauxhall Victor.

At first, coal fires heated each room. But oil-fired central heating and radiators, fuelled via an oil tank installed at the back of each house, replaced the coal and the coal scuttle. Large British Petroleum tankers pumped oil to the tank via a large pipe. Oil prices rose but electricity and gas, supplied by state-controlled bodies, remained affordable to most people on average and lower incomes.

Electric and gas fires supplemented the central heating.

Grass, flowers and shrubs flourished in back gardens.

I climbed trees. Munched sweet apples. Endlessly played football and cricket.

Rode my bike.

In summer, Colin, Mark and I pelted apples and pears at each other.

We built bonfires for Guy Fawkes Night every fifth of November – and we’d chuck fireworks at each other.

Little ones.

Snow always fell around Christmas.

We threw snowballs at anyone.

*

*

Affordable homes

Only one household lived in each home.

Household types consisted mainly of married couples with children, elderly couples, and widows or widowers.

All households owned their homes. Nobody rented.

The working families of Anywhere Gardens paid less than £5,000 for their semi-detached houses in the 1960s.

Some borrowed money from their parents and in-laws to stump up a deposit. They took out small mortgages from the bank.

People bought houses as homes to live in where they and their children could try to live happy, fulfilling lives and build a secure future.

People earned more income from their jobs and savings than from any value dividend on their houses.

On their death, their children would likely inherit these homes. Some descendants would continue to live in the family home. Others would sell only to buy a similar house nearby.

But people’s futures did not depend entirely on house values. Younger people could work and save enough for a deposit.

They could secure an affordable mortgage with comfortable monthly repayments to buy their own reasonably priced and comfortably spacious home.

If people could not afford to buy their own home, they could place themselves on a waiting list for one of many local council homes.

Taxpayer-funded homes offered at subsidised rent.

Managed and maintained by appointed officers employed by the local council. Directed by democratically elected local councillors.

Both private and public housing allowed local networks of families, friends and neighbours to remain intact and gradually evolve.

All these people.

All these lives.

Played out in an outlying suburb of London.

On the fringe of the capital city of a proud manufacturing nation.

A country primarily economically dependent on exporting goods made in Britain.

True, a capitalist economy initially founded on the exploitation of working people at home and in overseas colonies – and entirely based on profit. But one where social expenditure on council housing, the National Health Service and a welfare safety net for the poor were deemed necessary and desirable.

Unemployment, low pay, poor terms and conditions, and homelessness were viewed as enemies of social cohesion.

Jobs allowed people to make a decent living and allowed manufacturers to produce goods for sale and export.

Money was almost entirely used as a medium of exchange.

Banking and finance primarily served the ‘real’ economy of manufacturing, publicly owned industries, jobs, lives and hopes.

*

A north London village

Nearby, a parade of small individual shops served as a focal point for this north London village.

A greengrocer loaded fruit and veg into small, crinkly brown paper bags. People queued as a burly red-faced butcher chopped their meat to order.

The parade included a hardware supplier selling everything from ‘four candles’ to ‘fork handles’.

Also, a chemist. Newsagent.

Confectioner. Toy shop. Dress shop.

Hairdresser. Launderette. And over them all, hung the intoxicating aroma of fresh bread from Penny’s, the baker.

A family also ran a small sub-postmaster’s office, inside the newsagent, on behalf of the state-run Post Office.

Postmen delivered a ‘first’ and ‘second post’ at regular times each day to every house on each local street.

To earn a small crust, ‘paper boys’ rode on bikes before school delivering daily newspapers to many houses.

Milkmen from United and Express Dairies delivered milk, bread, orange juice and full cream from whirring electric floats to almost every home.

Let’s not forget Tony – the ‘Egg Man’, delivering eggs.

A friendly elderly couple – Jehovah’s Witnesses bearing Awake and Watchtower – regularly sought to deliver salvation to forsaken suburban sinners.

*

Supermarkets simply did not exist.

Independent local family-run shops predominated. Chain stores stood few and far between. Woolworths. Wimpy. Clark’s shoes.

Shops even shut for ‘early closing’ on Wednesday afternoons. Only the launderette opened on lazy Sundays.

The bells of the nearby Anglican church chimed every Sunday morning. The ‘last orders’ bell of the local pub clanged every night.

‘Bobbies on the beat’ patrolled the neighbourhood. Serious crime remained rare.

As a kid, I rode my Pavemaster bicycle along every neighbouring street – staying outdoors unsupervised for hours on seemingly endless hot Summer days.

In Winter, we’d play football in one of the many local public parks until darkness gathered.

The ‘Parky’ would shout at us, ‘I’m closing the bloomin’ gates, so bugger off home!’

Having endlessly replayed the 1973 FA Cup Final in our imaginations, we would ‘bugger off home’ – through gathering gloom in clothes caked with cloying mud.

*

School daze

This 2oth Century suburban village seemed safe for kids.

There was no mean and polluted ‘school run’ as in the 21st Century. ‘Rush hour’ lasted less than 35 minutes.

We’d walk for five minutes to reach our modest yet modern primary and junior school. A ‘Lollypop Lady’ ensured we crossed the road safely.

Some 400 pupils enjoyed spacious classrooms, four playgrounds and playing fields with two football pitches.

Two other primary schools offered similar facilities nearby. These schools easily accommodated the number of local children.

School days melded into a stream of immensely fun playground games.

British Bulldog. Off-ground It. Sliding on Winter ice. ‘Spot’, kicking against the wall football.

School life trundled between rituals – Sports Day, School Fete, Harvest Festival and a Nativity Play.

Looking back, school life seemed hazily blissful, a happy daze.

*

Few people celebrated Halloween but most households commemorated Guy Fawkes Night.

‘Remember. Remember. The fifth of November. Gunpowder, treason and plot.’

Boys, in particular, pushed stuffed Guy Fawkes effigies around the streets on prams or go-karts.

‘Penny for the Guy, Mister?’

Bonfire night.

Fireworks flew and sparklers flared in back gardens. Bangers blasted. Bangers of the meat kind flipped and sizzled on make-shift barbecues.

In the weeks before Christmas, unsupervised boys and girls spontaneously knocked on doors to screech carols in return for a few pence.

Or a ‘get lost!’

*

Rosy

Most families had lived in the area for generations.

Many people had previously lived in other parts of London or the United Kingdom.

A much smaller number had emigrated to Britain from the British Commonwealth – newly independent countries that used to be former British Empire colonial possessions.

Everyone spoke with a distinctive accent. But everyone spoke English.

Neighbours shared gossip over tea and biscuits. Often they mixed socially. Children called adult next-door neighbours ‘Uncle’ and ‘Auntie’.

On wintry days, families built snowmen and threw snowballs.

On hot Summer days, people tended gardens. Washed cars. Sunbathed, listening to pop music or news trebling from transistor radios.

*

However, life was not entirely rosy in this north London suburban garden state. Strife in the ‘outside world’ weighed heavily against this childhood idyll.

Money proved tight. Family life had its up and downs.

Owners let dogs crap on grass verges and did not clear up the mess. People smoked on local buses and on tube trains.

Colour ‘telly’ turned a black and white world into a blaze of glory but only two channels entertained – BBC-1 and ITV.

Even in colour, BBC-2 looked grey.

But most jobs remained secure and relatively plentiful.

People saved for rainy days and for their pension pots.

*

Strife

This placid idyll couldn’t escape the economic, political and cultural turmoil that characterised 1960s and 70s London.

BBC’ Radio’s World at One and ITV’s News at Ten reported ugly problems arising in London and the rest of the UK.

Anxiety grew over rising oil prices.

Endless strikes and bad industrial relations made life difficult.

Nationalised industries suffered from a lack of investment and industrial democracy.

Colonial ‘Troubles’ in Northern Ireland fatigued people. Terrorism – bombs in London and hijacked planes abroad – tested people’s stoic natures.

Weekly football fan hooliganism seethed.

The Cold War gloomed over everything.

‘Race’ and immigration angered.

UK parliamentary party politics achieved little more than antagonising London’s deeply ingrained class-based divides and inequalities.

*

Idyllic

As a young kid, I’d see this trouble, strife, suffering and antagonism on the TV news.

But then I’d look out of the front window.

There’d be just a few birds twittering amidst the cherry blossom.

As a kid, I’d think: “Where’s all this stuff going on?”

Life in an ordinary London suburb seemed idyllic – and felt like it could go on this way for generations.

Unchanged.

Forever.

*

© Paul Coleman, London Intelligence, 2014

*

Singing London

‘Lazy Sunday afternoon

I’ve got no mind to worry…

Close my eyes and drift away’

Song: ‘Lazy Sunday’

Performers: Small Faces

Songwriters: Steve Marriott/Ronnie Lane

Lyrics: © Intermediate EMI

Recorded at Olympic Studios in Barnes in 1968, Forest Gate-born Steve Marriott, and Ronnie Lane, born in Plaistow, wrote the psychedelic pop/music hall ‘Lazy Sunday’ about feuds with neighbours.

The Small Faces filmed a ‘Lazy Sunday’ promo at the home of drummer Kenney Jones’ parents on Havering Street in Stepney, east London.

A commemorative plaque on Carnaby Street (below) honours the Small Faces and manager Don Arden.

© London Intelligence, 2014

**