Crossrail

Without doubt the single most anti-productive thing we do is to shift millions of people back and forth across the landscape every morning and night…Right now, millions of commuting workers come home at night and flop down in front of a TV. That’s an isolating experience…Because of commuting many of our suburbs are social graveyards.’ – Alvin Toffler

By Paul Coleman

It’s not a delay if you stop to sharpen the scythe.

Delay remains preferable to error.

However, such clichés don’t easily hitch to Crossrail, London’s new east-west railway. It’s autumn 2018. Crossrail should now be all set for a full operation of new train services. Crossrail’s Elizabeth Line tunnels, tracks and trains are all ready. But in late August the government and Transport for London announce Crossrail will be delayed by ‘nearly a year’.

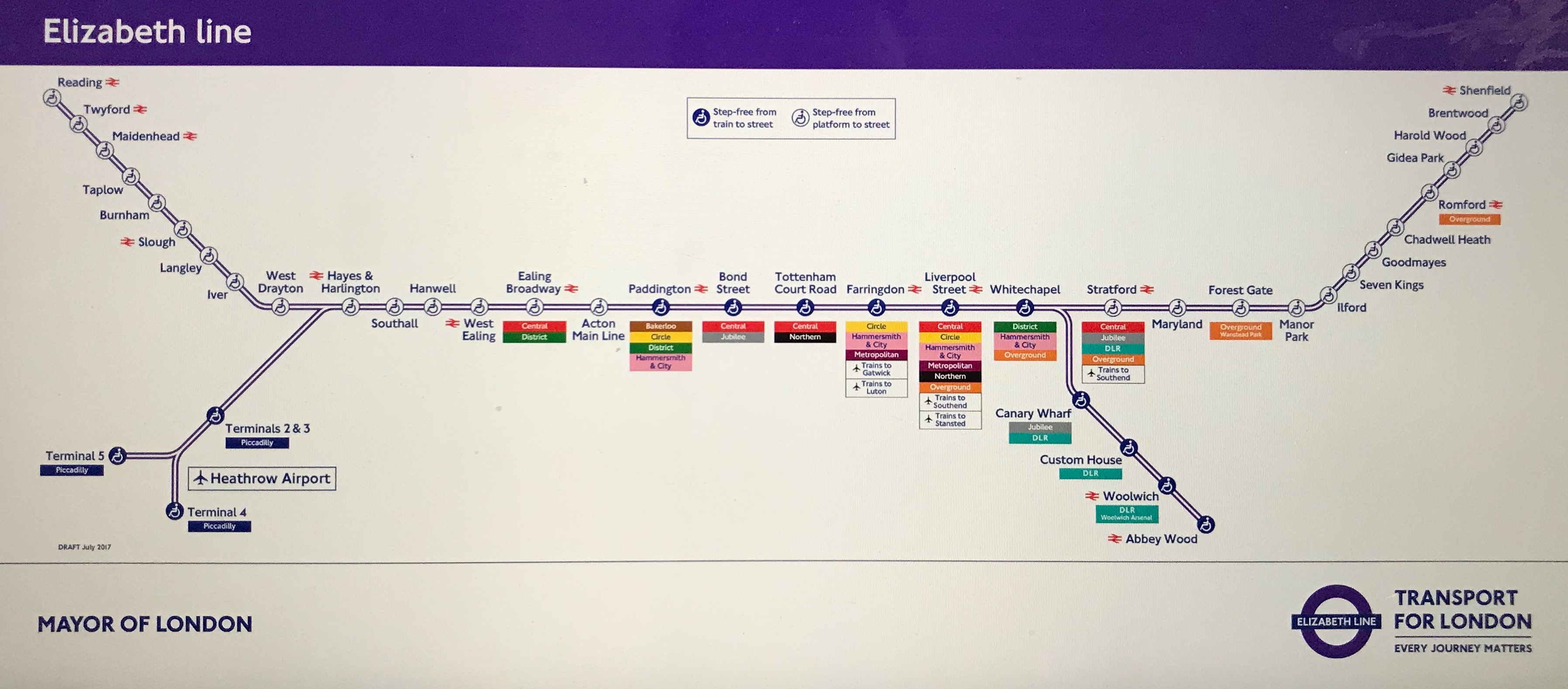

The delay and a cost over-run embarrasses London’s political establishment. The government and TfL are allocating £15.4 billion of taxpayers’ hard-earned money to Crossrail. Ten years ago, both central government and London’s City Hall promised Londoners they would deliver a life-changing railway on-time and on-budget. They heralded Crossrail as entirely good news. London’s ‘great white hope’ new railway will slash tedious journey times across the city. It will connect Paddington to Canary Wharf in just 17 minutes and bring an extra 1.5 million people to within 45 minutes of central London.

The mantra continues. More than 200 million passengers will use Crossrail every year but the railway will stop commuters having to pack like sardines onto overcrowded tube trains. Crossrail will add 10% to London’s rail capacity via forty-one step-free stations, with ten newly built and 30 upgraded.

The railway will provide and support thousands of jobs and apprenticeships – and feed off a supply chain based all over the UK. Last but not least, the government and TfL ‘guesstimate’ Crossrail will deliver economic benefits worth £42bn to the capital’s economy.

The new railway may still achieve and even exceed such aims but, in this gloomy 2018-19 Brexit moment, the glossy good news Crossrail narrative has hit the buffers.

*

Luck and love

London’s politicians and planners have long glossed over Crossrail’s deeper impacts on Londoners. It is true that Londoners compelled by rising house prices and rents to move out of the capital will need to use the Elizabeth Line to commute to and from their jobs in central London.

But, ironically yet inevitably, Crossrail triggered a significant proportion of London’s house price and rent rises. Crossrail inflated demand for houses along its route from Reading and Heathrow in the west to Shenfield and Abbey Wood in the east. Estate agents serving markets within a one kilometre radius of new Crossrail stations could not believe their luck.

Developers love Crossrail too. Almacantar say Crossrail will help it to handsomely profit from their high-end luxury Centre Point apartments. Centre Points sits right on top of the Crossrail station at Tottenham Court Road. Centre Point and Tottenham Court Road will be the only point across London where Crossrail will meet with Crossrail 2, a proposed north-south London rail link.

“Crossrail is a massive pull,” says Almacantar communications director Daniel Ritterband. “It’s four minutes from Mayfair, six minutes from the City. That infrastructure lights the torch paper and inspires developers and others to move in.” Ritterband points out Facebook, Warner Bros, LinkedIn and Twitter have taken office space within three minutes walk of Centre Point and Tottenham Court Road’s Crossrail station.

*

Obsolete

There’s a wider question too. Is the need for such a vast new railway obsolete? Elizabeth Line services are poised – delays pending – to start running at a time when Londoners are told they live and work in a ‘knowledge-intensive and post-industrial’ era.

New communications technology means knowledge is mobile. Many predict this signals the ‘death of the office’, the nine-to-five working shift, and the ‘work-bed’ commute. Pardon the pun but, according to this train of thought, Crossrail is already obsolete even before its Elizabeth Line trains trundle out of their depot.

Elizabeth Line trains might start running in late 2019 when capital in London might no longer need skilled labour in the same numbers, at the same time and at the same place. Londoners are told they can increasingly work from their own homes – their Toffleresque ‘electronic cottages’ – as new technology and flexible rosters render daily commuting and nine-to-five office shifts far less necessary.

Employers, politicians and economists say plant, machinery, raw materials and labour are diminishing on capital’s list of necessities. Knowledge is the dominant component of production in London. New technologies, such as digital communications, automated cars, vans and buses, artificial intelligence, cybernetics, robotics, bioengineering and materials science, constantly change the way Londoners work – and often replace labour as a factor of production.

*

*

Rumours

However, reports of the arrival of this brave new future in London might be premature. Even a knowledge-intensive economy needs humans to transform data and information into programmable knowledge. Apparently, the worker still needs to be moved to the information by new tunnel railways like Crossrail. Many commuters work in the City of London in finance, banking and insurance. The City’s population during the working day is about 358,000, according to government statistics – that is over 59 times greater than the City’s resident population of 6,000. Rumours of the ‘death of the office’ appear to be greatly exaggerated. Three quarters of working people still work in offices.

This is borne out by the large numbers of Londoners who commute from outlying boroughs to what planners call London’s ‘central activity zones’ – the City, ‘Tech City’, Royal Docks, Canary Wharf, Stratford, the West End, London Bridge, Croydon, Brent Cross, the ‘Golden Mile’ in Hounslow, and Heathrow Airport. For instance, Lewisham’s workday population falls by almost 30% from 206,000 to 149,000. (1)

Londoners know and loathe congestion. So, it’s easy to see why many Londoners eagerly anticipate Crossrail’s relatively impressive reduced journey times. Commuters from the Berkshire town of Reading to the west of London will be able to reach Tottenham Court Road in London’s West End in 55 minutes. Bankers at Liverpool Street at the heart of the City of London financial district will be able to reach Heathrow Airport to the west of London in just 41 minutes. Commuters in the eastern suburb of Harold Wood can reach Bond Street in 40 minutes.

Crossrail – the Elizabeth Line – promises Londoners respite from their daily stress as they commute to their daily bread. But at £15.4bn, it’s a promise that Londoners demand must be delivered.

Capacious

Around 800,000 enterprises of all kinds and sizes operate in London, employing more than 600,000 Londoners. The public sector alone – civil service, health, education, local government and emergency services – employs 739,000 people. Voluntary and community organisations employ another 377,800 people. (2) An efficient and capacious transport system is vital.

Capital in London also requires humans to be consumers as well as commuters. Centres of consumption are ubiquitous in London; almost every new housing and office development seems to include a retail element. Shopping is London’s growth hobby. Hence, Crossrail will serve capital’s need for ever-expanding consumerism. The Elizabeth Line will funnel consumers into tunnel stations close to shopping cathedrals at Canary Wharf, Stratford (for the vast Westfield mall) and to Bond Street and Tottenham Court Road, two underground stations that serve Oxford Street, one of the world’s busiest and iconic shopping thoroughfares.

Crossrail itself will also almost inevitably become an advertising platform. Elizabeth Line trains, platforms, walkway tunnels, escalators and gate lines will be sold as advertising space to pump individualism, consumerism and the illusion of choice – leisure, pleasure, style, sexuality and international humanism – into the minds of captive legions of commuters, consumers and tourists.

Of course, a consumerist London society also needs platoons of workers to serve consumers in its shopping malls and refresh them in the ‘barista’ service economy. Certain types of production in London will always need labour. Knowledge alone, of course, cannot build a house, bake bread, brew a cup of coffee, or cook a meal for an elderly person in their home. This labour is needed in position. Hundreds of thousands of Londoners still need to shuffle back and forth across their city.

Commuting for working Londoners might be anti-productive and an unpaid, deadening routine that wastes time and fuel and spawns pollution and overcrowding but Crossrail promises to turn that daily shuffle into a swish with faster journey times in less crowded trains. The new railway aims to zip commuter hordes between London’s primary centres of production – Heathrow Airport, the West End, the City of London financial centre, Docklands, and Stratford – and residential neighbourhoods in Greater London’s outlying suburbs and satellite towns.

*

Champions and detractors

Politicians, rail and construction functionaries, developers, estate agents, architects, engineers and some vocal Londonphiles champion Crossrail as a publicly funded £15.4 billion railway that will grandly serve a public whose taxes pay for it and whose fares sustain it. For instance, New London Architecture, a planning and architectural forum based near one of Crossrail’s new central hubs at Tottenham Court Road, states: ‘By 2030 London’s population is set to reach 10 million. The city and its transport system, already one of the busiest globally, has to be ready to handle this increasing demand. To help meet this challenge and maintain London’s place as a world-class city, the Elizabeth Line will increase London’s rail capacity by 10%, ease congestion and speed up journey times.’

Crossrail’s detractors say that capital will rapidly no longer need the mass commute to make profits as knowledge-intensive production requires less labour. Some Londoners, politicians, and disgruntled Londonphiles say Crossrail’s principal beneficiaries will be well-paid financial sector functionaries in the City of London and Canary Wharf. City business travellers will no longer need to sit in the back seats of fleets of chauffeur driven cars as they criss-cross the city between Canary Wharf and the City of London and Heathrow Airport. In this outlook, Crossrail is seen as a publicly funded railway that subsidises the narrow interests of an already wealthy sector of London’s economy – the people who work for the very institutions that spawned the catastrophic financial meltdown of 2007-09 that in turn led to the ideologically driven austerity cuts to public sector jobs and services.

Does Crossrail stem or extend inequality in London?

Crossrail is under the control of London’s elected Mayor who strategically directs Transport for London. In turn, Transport for London wholly owns Crossrail Limited, a company that is responsible for building the Elizabeth Line. Crossrail receives taxpayer and farepayer funds through TfL, the Greater London Authority and from central government. Crossrail also receives some funding from property developers. Towards the end of construction, taxpayers are told they can expect surplus income generated from profits made on land and property developments. TfL will take control and integrate the new railway into London’s transport network.

*

Uneven development

But who wins and who loses with Crossrail?

A cost benefit analysis is commonly used to justify Crossrail’s £15.4 billion outlay. The business case for Crossrail estimates the railway will produce £1.97 of benefit for every £1 of cost, through reduced journey times, reduced crowding on London’s other public transport modes and quicker interchanges between services.

This cost benefit analysis claims the new railway adds an estimated £42bn to the UK economy. Faster journey times will boost productivity. Crossrail also says it expects to create 75,000 business opportunities, generating enough work to support the equivalent of 55,000 full-time jobs.

Crossrail claims that it has awarded 95% of its contracts to UK companies – and 61% to companies outside of London, countering claims the new railway inherently represents uneven development by benefitting only London.

Crossrail also says it has employed some 10,000 people working at more than 40 construction sites and that by 2016 it had created over 500 apprenticeships. In May 2017, Transport for London (TfL) introduces a fleet of 66 Class 345 trains built by Bombardier in Derby – a train-building contract that supports 760 UK jobs and 80 apprenticeships.

TfL has awarded a £1.4 billion eight-year contract to MTR Corporation to operate Crossrail services. The Hong Kong-based corporation is expected to employ 1,100 staff on Crossrail, including 400 drivers, and provide 50 apprenticeships for local people along the route. Skilled Bombardier railway workers will maintain and service Crossrail’s 66 trains at an Old Oak Common depot.

Crossrail also creates a skills legacy – a £13m tunnelling and underground construction academy in Ilford that has trained over 15,000 people since opening in 2011.

*

Property boost

Indirectly, Crossrail also says it is ‘helping to drive regeneration along its route’. Crossrail’s executives say the new line will support the delivery of over 57,000 new houses’ and 3.25 million metres of commercial space. It says research shows the railway ‘could help create £5.5bn in added value to residential and commercial real estate’ along the route up until 2021. Crossrail proudly says nearly half of planning applications within a kilometre of an Elizabeth Line station cite the new railway as a justification for the development proceeding.

Twelve major property developments are being built over and around Crossrail’s new central London stations, generating much excitement amongst property developers and their architectural and planning functionaries. ‘The new stations and public space, homes, office and shops developed around them will add to the fabric of the landscape, act as a catalyst for regeneration and influence the way people experience the city and its suburbs,’ chirps the NLA.

“Crossrail is the most important thing to have happened to Ealing since the growth of the borough in the early 20th century,” says Pat Hayes, executive director for regeneration and housing at the west London borough of Ealing. “We’ve gone overnight from being a zone 3-4 borough, effectively to being a zone 1,” adds Hayes. “Areas like Southall could become the ‘new Brixton’ given the area’s edge, diversity, interest and new accessibility. No-one would have taken the risk to build 4,000 homes on the Southall Gasworks site without the catalyst of Crossrail.”

*

Property inflation

It is this aspect of Crossrail – its entirely foreseen impact on London’s unregulated property market – that fuels an accusation that one of Europe’s biggest ever civil engineering projects also sires crude and destructive social engineering along its route. Rather than make life easier for working people, Crossrail shreds the social fabric of London life for a significant number of people and businesses – and acts as a catalyst for house price inflation that means people on average and lower incomes cannot afford to live in London and its suburbs.

By raising rents and property prices and values, the east-west rail link inspires an outbreak of unprecedented opportunistic greed on the part of land and property freeholders, leaseholders, homeowners and landlords. Crossrail’s rip tide of rising property values sweeps away smaller leaseholders running viable and vibrant London enterprises.

Many owners and occupiers voice dismay with compensation levels that mean they cannot afford to re-establish their businesses and venues in other parts of central London. Other businesses and home-owners feel the force of Crossrail’s compulsory purchase regime – which although extends the usual period to enter an acquired property from two weeks to three months – still means the end of their occupancy and ways of life. These compulsory purchase orders allow Crossrail to demolish these properties and build its twin-ended stations, ventilation shafts and ‘over developments’ of new offices, homes, shops and open spaces.

For instance, Crossrail forces the closure and demolition of long-established and independent Soho shops, cafes, restaurants and music venues to build its vast Tottenham Court Road and Bond Street stations. People working in Soho’s performing arts industry campaign against Crossrail raising property and rent values to levels that can only accommodate executive offices, luxury flats and chain stores. They fear Soho is becoming like Camden Town, where chain stores and rising house prices are dissolving a diversely active working class enclave, turning the area into the bland ruin of an ‘anywhere town’, characterised by ubiquitous coffee shops and supermarkets.

Crossrail also fails to provide a detailed breakdown of where those 57,000 homes will be located and what proportion will be genuinely affordable for Londoners on average and lower incomes. For instance, at Whitechapel and Woolwich, Crossrail is blamed – but praised by property owners – for ongoing house price increases of over 50% since 2014. Ilford, Forest Gate and Abbey Wood to the east of London and Slough and Southall to the west fare similarly.

Crossrail says house prices immediately around its central London stations will rise by 25% and 20% near its suburban stations. Property consultants differ marginally but generally enthuse that Crossrail generates house price inflation along its route, stating variously that Elizabeth Line prices could rise by 36% on average by 2020 – and that house prices will rise by an average of £133,000 even before the first trains run in late 2019.

*

Crossrail 2 – the sequel

Crossrail begets winners and losers. Finance and retail capital definitely gain as Crossrail promises to deliver their daily producers and consumers more efficiently. These elements of London’s workforce ought to therefore enjoy some of Crossrail’s benefits – faster journey times and an improved start and finish to their working days. Crossrail’s tunnelling and construction academy also shows how infrastructure of this scale and type can benefit all Londoners with a reproductive legacy of skills and training. But the Elizabeth Line’s indirect inflationary impact on London property prices reduces life chances for many Londoners.

Crossrail also has a planned younger sequel, Crossrail 2 – a politically backed new railway running north to south through central London and connecting Hertfordshire and Surrey due for completion in 2033. Crossrail 2 could also help working people in London. But it could help much more if London’s economy is revived and rebalanced with significantly scaled investment in new manufacturing industries and in public sector jobs and services – especially those services that require more skilled and non-skilled labour.

Delivery of such benefits for labour would depend on Crossrail and Crossrail 2 remaining affordable and efficient. If not, both new railways could become ‘white elephants’, an expensive travel mode serving mainly the elite well-paid functionaries of capital to travel – just like many of the UK’s intercity train services that price out people on average and lower incomes.

Finally, an increase in the supply of genuinely affordable new homes and controlled rents would also help Crossrail and Crossrail 2 to reduce rather than extend inequality in London.

The new railway’s detractors can only hope that future major infrastructure projects impacting upon Londoners undertake more penetrating social cost benefit analyses rather than just focus on surface-level economic benefits and costs.

References

1. Office for National Statistics, 2016

2. Greater London Authority, The London Plan 2016, (London, Greater London Authority, 2016, Chapter Four, paragraph 4.5.

The new railway facts and figures

*

Words and Photos © London Intelligence.

London Intelligence ® is a registered trademark of London Intelligence Limited.