Grenfell: before the fire

The Grenfell Tower fire of June 2017 killed 72 working class Londoners, including 18 children.

Will a police criminal investigation and a public inquiry reveal the historical ‘regeneration’ context that led up to this catastrophe?

By Paul Coleman

It’s shortly before one o’clock in the morning on Wednesday 14 June 2017.

The London Fire Brigade receives the first of some 560 emergency 999 calls.

Callers report a fire at a residential tower block on the Lancaster West Estate in north Kensington.

The tower is Grenfell.

*

Magnitude

Thirty minutes or so later, sections of all four elevations of the 24-storey tower are ablaze.

Up to 600 men, women and children live in the block’s 129 apartments. Many are trapped inside.

They make emergency 999 calls. They phone family and friends and send texts. Some post video clips on social media, including from the 23rd floor.

Toxic carbon monoxide and lethal hydrogen cyanide fumes plume into the air and billow upwards into the west London skyline. Fire crews race to the scene. On first seeing the burning tower, some fire-fighters express utter disbelief. One says: “There’s kids in there…how has that happened?”

Fire-fighter Matt Sephton and his crew from Hammersmith fire station arrive at the tower at 01:10. “There was a small kitchen fire going from the fourth floor all the way to the top floor,” recalls Sephton. “I was shocked; it was an unusual situation.”

*

Thick black smoke

Sephton dons his breathing apparatus and leads a crew of colleagues up a Grenfell Tower staircase. They begin fighting a fire already rapidly engulfing the entire block. Fire means the lift cannot be used. A narrow central staircase is now the only way up and down.

Inside the 70-metre-high tower Sephton and his team-mates cannot see how far and fast the fire spreads. “You couldn’t see anything,” recalls Sephton. “It was just thick black smoke.”

Sephton only realises the magnitude of the fire when he leaves the tower. “It was like, wow, what is going wrong, what has happened here? It was a massive fire by then, properly shocking…the whole building’s alight.”

Fire crews see Grenfell fire for first time…

*

Great distress

Mahad Egal lives with his wife and two children on the fourth floor. “We had just eaten, it was Ramadan, and we were preparing to sleep,” says Egal, recalling his escape.

Egal’s neighbour from flat number 16 alerts him to the fire. Putting wet towels on his children’s heads, Egal and his family leave the tower via that staircase. “As we come down, our neighbour explains his fridge had exploded,” says Egal.

Outside the tower, a woman sits on the ground in great distress, saying her ‘five-year-old child is missing’.

Local resident Victoria Goldsmith recalls two people trapped at the top of the tower flashing their mobile phone lights. “They were trying to signal to people,” says Goldsmith. “But nobody could get to them and the lights just went out”.

Two women say they have heard people screaming for help from within the tower. They take bottles of water through a police cordon.

Clusters of local people gather in adjacent streets. At just before four in the morning local resident Tim Downie says “bemused and shaken” barefooted people, evacuated from the tower, stand on the street in their nightwear, holding their children. Others hold cats and dogs. “They stand watching as their entire lives go up in flames,” recalls Downie.

People jumped

At 04.30 residents tell police officers they are receiving calls from people still trapped in the tower. Police say they must tell trapped family and friends to place wet towels over their heads and get themselves out of the building. The emergency services euphemistically call this ‘self-evacuation’.

At around 05.15 estate residents crowded on the streets see a man trapped inside the still burning tower on the 16th floor.

Eyewitnesses to the fire are clearly traumatised. Tamara, a local resident, recalls: “Several of us ran over to the estate. People were throwing kids out of the building and saying ‘just save my children’.”

“I saw a man fly out of his window,” says Samira. “I saw kids screaming for help and people jumping out.”

“People jumped,” says a fireman. “A mother threw a baby from a floor high up, caught by a complete stranger just so she could get her baby away from the fire.”

A young man closes his eyes and puts his hand on his forehead. “I saw a kid on fire on the twenty-second floor,” he says. “The kid walked to the window and jumped.”

Ran for life

“I was in bed,” says Eddie Daffarn, a Grenfell Tower resident on the 16th floor. “It was just past one o’clock. I’d been listening to a radio programme. I then heard my neighbour’s smoke alarm. I was unconcerned. I just lay in bed thinking they’d just burnt some chips or something.

“A minute later I heard a commotion out in the hallway in the communal area outside my flat. That was unusual. I got out of bed, threw on some clothes, pulled open my front door expecting to see my neighbour outside.

“This thick, acrid smoke just came flooding into my flat. I just closed my door straight away and my heart just sunk. I think I’ll probably just stay in my flat – as that’s what we’ve been told to do. And literally, as I was thinking that, my phone rang. It was a neighbour from downstairs and he shouted at me:

“Get out. Get out!

“And he said it in such a forceful manner that I didn’t question him. I ran to my bathroom. I got a towel and wet it, wrapped it around my face and came back to the front door. I’d picked up my keys and phone as a force of habit – not in a thinking way – and came out into the hallway. I closed the door behind me and was then faced with total darkness.

“I couldn’t see beyond the end of my nose. I had to make my way to the emergency exit about five metres diagonally over the other side of the communal area. I remember little about it. Instead of finding the door which would lead me to the emergency stairwell I found a piece of ‘boxing-in’ – part of the improvement works. I was literally just pawing at the wall, instead of logically thinking to find the door.

“I let go of the towel and it fell. I’m thinking I’m not going to get out of here. Just at that moment, I think I had three or four more breadths left. Then a fireman came through the emergency doorwell. My next door neighbour had gone down and asked the fireman to go up and rescue a relative who had been unable to leave their flat – and that’s the sole reason why the fireman was there at that time.

“The building was not full of firemen at that time so the chances of it happening were just one in a million. So I was able to escape into the emergency stairwell and then – to be honest with you – I just ran for my life. I passed a couple of people on the stairs. I passed my neighbour who’d asked the fire brigade to rescue his relative.

“I remember little of my exit from the building, particularly the lower levels. I remember being just outside, next to the sports centre about 50 yards from the building.

“At that time – around 1.20am or 1.25am – the building was ablaze in the most catastrophic way – heartbreaking.”

72

Daffarn’s recollection proves horribly apt.

The Grenfell Tower fire is a heartbreaking catastrophe.

The fire kills 71 people. A 72nd victim – Maria De Pilar – rescued from the 19th floor, dies in hospital in January 2018 from complications sustained as a result of the fire.

Eighteen children are amongst those killed.

Seven of those people killed are aged over 70; the youngest are babies, one stillborn and the other six-months.

Of 54 adults killed, 29 are women and 25 men. The oldest victim is an 84-year-old man.

The police say 62 victims lived in 23 of the tower’s 129 flats. These flats are between the 11th and 23rd floors.

Four people killed do not live in the tower.

Some people only get confirmation their loved ones are dead months after the fire.

Disaster

The Grenfell Tower fire causes the worst single loss of life in the United Kingdom for 30 years. It is the worst civil disaster in the UK in the 21st Century – and the most calamitous fire seen in a London residential building since World War II. It is the worst loss of life by fire since 167 were killed on the Piper Alpha oil platform in July 1988.

It is the worst ever disaster to befall public or council housing in Britain – although it is not without precedent. The Ronan Point gas explosion and partial building collapse killed four people in 1968. The Lakanal House fire in south London of 2009 killed six people. Worse still, fire safety recommendations that followed Lakanal House were ignored. Had they been implemented, the Grenfell Tower fire could almost certainly have been avoided.

The Grenfell Tower also leaves a shocked west London community in absolute grief. Grenfell was home. A human space for unique working class individuals and families. It was their place of refuge and a joined up community. They lived together – and many died together.

One year later, many surviving and impacted Grenfell families – often with children – still live in temporary hotel accommodation despite London – and specifically, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea – having large numbers of empty and under-occupied homes.

A lethal refurbishment

Global media relays images of the Grenfell Tower fire across the planet. People want to know how and why did the fire spread so far and so fast.

Police quickly rule out arson. Police state the fire started in a Hotpoint fridge freezer (FF 175BP) in the kitchen of Flat 16 on the fourth floor on the tower’s east elevation at sometime around 00:54.

They establish manufacturers and distributors are not subjecting this model to a product recall. Later – months later – a leaked report will say flames from the fridge-freezer flared towards a window one metre away.

The flames inside that one flat reportedly found a route through a window frame to set light to Grenfell Tower’s exterior cladding and insulation. By 01:29 the exterior flames reach the top floor on east elevation. By 02:51 all four elevations are on fire.

The last resident to escape does so at 08:07. At 19:55 the incident commander says no more lives can be saved.

The disaster happened because of the lethal refurbishment of the Grenfell Tower. A flammable exterior cladding and insulation system is the main feature of the tower’s refurbishment that began in 2014 and completed in 2016.

In that year a dire warning is sounded to the building and construction industry about such cladding and insulation systems.

Tarling’s warning

That warning is sounded by Arnold Tarling BSc FRICS MCIArb of Hindwoods Chartered Surveyors. Tarling is a member of the Association for Specialist Fire Protection that advises an All-Party Parliamentary Fire Safety and Rescue Group. Tarling says he issued a strong warning in 2014 that cladding systems – allowed under slack building regulations – would cause major loss of life.

At first seeing TV news images of the fire at 03:45, Tarling recalls: “To be honest, I burst into tears. This tragedy is totally avoidable. I would say it is wicked that these people have had to die…The people responsible are either the politicians or their advisors. It need never have happened.”

The specialist says the polyaluminium cladding is basically two sheets of metal with a filling of polyethylene. The polyaluminium, which melts at 600 degrees, initially shields the burning polyethylene from any attempts by firefighters to extinguish the fire. “Polyethylene is like a candle,” says Tarling. “It melts at 120 degrees and it burns.”

“You also have a wind tunnel effect sucking the flames up between the insulation and the external cladding…continuing the fire right up the height of the building.

“So, basically, you have a candle installed on the side of a building with the wind and the air movement causing the fire to spread rapidly.”

Building regulations

Tarling condemns the standards set by Building Regulation in regard to this form of cladding. “All that you require to meet the standards is that the outside surface shouldn’t allow the spread of flames,” says Tarling. “What is going on behind the metal or the other surface is entirely irrelevant to Building Regulations.”

He says the initial source of the fire in a single Grenfell Tower flat is “entirely irrelevant”.

Tarling says he has seen nothing yet to indicate the architect, building contractor or the material suppliers have breached these building regulations. “The horrendous fact is that in 2014 I did a talk to the British Standards Institution at one of their fire safety conferences where I said there will be multiple fatalities in this country if these cladding systems are not changed.”

Criminal

This patently flammable cladding consequently becomes the focus of intense scrutiny, speculation and fear.

Hundreds of other residential tower blocks, hospitals, schools and hotels are found to be clad in similar systems of flammable cladding and insulation.

One year after the fire, not a single person involved in making decisions about the Grenfell Tower’s refurbishment has been arrested, charged and held to account – despite a massive police criminal investigation.

But public scrutiny falls on the local authority’s political leadership at the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and on the salaried officers of the council’s appointed landlord, the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation.

The landlord

The Kensington and Chelsea Tenants Management Organisation is directly responsible for commissioning sub-contractors to carry out the refurbishment of the Grenfell Tower – including cost-cutting measures.

It is also responsible – albeit with the council – for ignoring fire service warnings about tower block fire safety and for failing to act upon the recommendations that followed the fatal Lakanal House fire of 2009. The KCTMO also ignored residents’ direct experiences and repeated warnings about compromised fire safety at Grenfell.

As landlord, the KCTMO failed in its duty to protect its tenants and to keep them safe.

Its chief executive is Robert Black.

The planning application for the Grenfell Tower’s refurbishment contained Black’s signature. The application turned a perfectly safe council house tower into a building cosmetically clad – largely for the sake of appearances – with highly flammable and combustible cladding and insulation.

The council

Elected local politicians on expenses and appointed salaried officers of the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea are responsible for scrutinising the KCTMO’s decisions. The leader of the council at the time of the fire is Nicholas Paget-Brown, a Conservative politician.

It is hoped that this trail of decision-making and scrutiny will be revealed by the police’s criminal investigation and by an appointed public inquiry headed by a senior former judge. It is feared that these trails will be concealed through corporate obfuscation and legal chicanery.

The justice road for the Grenfell victims, to their proving governmental and corporate malfeasance – even corporate manslaughter – will likely prove arduous and costly. For instance, the police say 60 companies are involved in the refurbishment of Grenfell.

After the fire, on 30 June, Paget-Brown steps down as leader, and is replaced in July by Elizabeth Campbell, another Conservative.

The KCTMO hands back the interim management of housing services to tenants and leaseholders to the council from March 2018.

Cladding and insulation

The cladding and insulation used to refurbish Grenfell Tower come under intense public scrutiny. Initial findings raise immediate grave concerns about the ‘rain screen’ cladding and insulation system used to refurbish the Grenfell Tower’s faces and columns. This system turns Grenfell Tower into a fire waiting to happen and an instantly concocted death trap.

After the fire, experts focus on a cavity between the cladding and the insulation. This air gap is designed to evaporate condensation that could damage the tower’s original pre-cast concrete exterior walls. However, it is widely believed this gap may have acted as a further funnel to help spread the fire.

Footage of the fire suggests this funnel or chimney effect acted fastest in the cladded columns that frame the tower from top to bottom. The funnel effect heats and sets alight the panels. In turn, this sets the insulation aflame. Toxic fumes, such as hydrogen cyanide, then overcomes residents.

In short, the choice of these cladding and insulation materials and their procurement as part of the tower’s refurbishment helps to spread the Grenfell fire and maximise its lethality.

Architects

Grenfell residents say they approved a fire-resistant zinc cladding as part of the tower’s refurbishment. But their approval is either overruled or ignored at some point.

The Grenfell refurbishment is designed by Studio E Architects. The practice says it proposed the cladding with its ‘fire-retardant polyethylene core’. But this fire-resistant zinc cladding is replaced in the refurbishment contract with combustible and flammable rainscreen panels – apparently to save a paltry £293,368.

Andrzej Kuszell, a founding director of Studio E Architects, faces intense scrutiny after the fire. Kuszell’s design created gaps that spread the fire and allowed flames to get into residents’ flats.

Studio E Architects also designed the Kensington Aldridge Academy school for 1,14o pupils built right next to the Grenfell Tower.

Main contractor

The main building contractor is Rydon, whose chief executive is Robert Bond. Rydon is responsible for the refurbishment’s ‘design and construction and for liaising with residents’. The company replaced an earlier contractor, Leadbitter, deemed sluggish and too costly.

Rydon stands accused of undercutting rivals to get the £8.5 million Grenfell Tower refurbishment contract and then of using cheaper materials. Rydon also reportedly fails to fill gaps at the side of windows that allows fire to spread inside.

Rydon also reportedly specifically suggests swapping non-combustible material for a cheaper flammable cladding.

This cladding also gives off highly toxic fumes when burnt. It is believed lethal inhalations of toxic hydrogen cyanide and carbon monoxide smoke killed most of the Grenfell Tower’s 72 victims. It also sets fire to the flammable insulation.

“That would be equivalent to having four large petrol tankers all full of petrol all burning at the same time on Grenfell Tower,” says fire science expert Professor Richard Hull.

Testing

Rydon had a legal responsibility to test what effectively was a new combined system of cladding and insulation. But were such tests carried out?

Robert Bond says the cladding was not cheap and dangerous but says the cladding was specified by the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea and was approved by the council’s building control department and by the refurbishment’s architect. Bond says Rydon did not carry out testing as the system was “deemed to have complied”.

“We worked 100 per cent, absolutely, within the regulatory framework,” says Bond, who says Rydon bears no responsibility for the dangerous state of the Grenfell Tower. “It’s an absolute terrible tragedy and my heart goes out to them.”

The cladding and insulation are reported to have never been tested anywhere. The manufacturers of both the cladding and insulation knew they were to be combined for the Grenfell Tower refurbishment. But they did not warn the refurbishment project of the risks.

Why not? Carelessness? Oversight? Or, worse still, for profit?

Suitability

Refurbishment engineering consultants, Max Fordham, says it specified another type of cladding as part of the original plans for Grenfell – Celotex FR5000 (FR denoting ‘Fire Resistant’). The consultancy later reportedly says the other type of cladding and insulation materials eventually used should not have been combined for usage on Grenfell.

Saint Gobain describes itself as the ‘leading UK PIR thermal insulation provider for the building and construction market’. The company says it supplied polyisocyanurate plastic insulation Celotex RS5000 for the Grenfell refurbishment but was not responsible for attaching it to the tower’s original pre-cast concrete exterior.

The company says fire safety testing of RS5000 was undertaken in 2011 under British Standards and achieved the highest performance national fire system rating – Class 0 – a regulation on building materials that specifies a very limited surface spread of flame as defined in Approved Document B, the guidance for Building Regulations in the UK.

Before the fire, the company marketed its product as suitable for use on ‘buildings with a storey height of above 18m’. But this suitability is now questioned. The firm also said its insulation product was suitable for use with a range of cladding product. That suitability is also questioned.

Was this insulation used on Grenfell ever tested for tower blocks? Were earlier tests actually carried out on insulation that contained extra fire retardant? Was a more flammable and cheaper version then sold for public use and corporate profit?

Certainly, what is now known, is that the insulation used on Grenfell is highly combustible and releases toxic fumes when it burns. In the days after the fire, burnt Celotex insulation lies all around the Lancaster West Estate walkways and across the communal gardens and balconies of the neighbouring Silchester Estate.

After the fire, on 23 June 2017, Saint Gobain stops selling Celotex RS5000.

Banned or legal

Fire safety specialist Arnold Tarling describes the use of such materials on tower blocks as “mindblowing” and “wicked”.

The cladding consists of aluminium composite panels arranged as ‘rainscreen cassette panels’. These panels sandwich two aluminium sheets. Branded as Reynobond, they come in two different forms; Reynobond E, with its polyethylene core that burns, and Reynobond FR, a fire retardant version with a mineral core.

These facades are supplied by CEP Architectural Facades, part of the Omnis group. The company says that the companies carrying out the refurbishment of the Grenfell Tower asked it to supply Reynobond PE cladding that is £2 cheaper per square metre than fire retardant Reynobond FR.

On 18 June 2017, the government’s Chancellor, Philip Hammond, tells the BBC: “My understanding is that the cladding, this flammable cladding which is banned in Europe and in the United States, is also banned here.”

CEP Architectural Facades managing director John Cowley immediately contradicts Hammond: “Reynobond PE is not banned in the UK,” says Cowley. “Current building regulations allow its use in both low rise and high rise structures.”

However, the government claims polyethylene-cored panels used to clad Grenfell failed to meet a higher combustibility standard, rendering their usage illegal. Yet in March 2012 a government fire safety expert reportedly signs a certificate that allows their use on buildings above 18 metres.

Contractors, builders and insurance companies say regulations do permit such cladding.

The manufacturer

Arconic manufactures the actual Reynobond panels. Some experts now say fire resistance tests should have required Reynobond PE to have attained a higher A rather than lower B rating. Manufacturers Arconic says it knew the tests ratings were low, even as low as E on some tests.

One anonymous expert source says in April 2018 “you wouldn’t put E on a dog kennel” and that the cladding should have been subject to a product recall.

Arconic stress it was not involved in the installation of the cladding system, nor in any other area of the tower’s refurbishment, but it confirms it supplied Reynobond PE used for the refurbishment.

Commercial relationships

The company’s statement after the fire shows the complexity of the commercial relationships involved in the refurbishment of one council house tower. Arconic says it supplied Reynobond PE to ‘our customer, a fabricator, which used the product as one component of the overall cladding system on Grenfell Tower.

‘The fabricator supplied its portion of the cladding system to the façade installer, who delivered it to the general contractor. The other parts of the cladding system, including the insulation, were supplied by other parties…We don’t control the overall system or its compliance.’

The company says it provides only ‘general parameters’ for the use of its products but says it sells them ‘with the expectation that they would be used in compliance with the various local building codes and regulations’. The panel manufacturer says ‘current regulations within the United States, Europe and the UK permit the use of aluminium composite material…’

Nevertheless, in stating its limited role, Arconic states: ‘In light of this tragedy, we have taken the decision to no longer provide this product (Reynobond PE) on any high-rise applications, regardless of local codes and regulations.’

Responsible

The British Board of Agrément issued the B rating for the cladding in 2008, using Arconic technical data. The BBA says its certificates are not ‘guarantees’ for individual buildings. The BBA maintains a local authority is responsible for deciding whether to use such materials on a building.

Local Authority Building Control, that represents council building control teams, says its members depend on manufacturers telling the truth about their products and tests.

The government says – since the fire – class A standard rather B ratings are required for buildings over 18 metres high. But construction industry sources say this guidance is only made clear after the fire and add government set the lower standard class B before Grenfell. Any material rated Class E ought to have been banned from use anyway.

Hampered

Not surprisingly, given the flammable cladding and insulation, the Grenfell Tower fire burns for 60 hours. Firefighter Matt Sephton is one of some 250 London fire-fighters at the scene. They push their courage, endurance and skills to the limit to save as many people as they can.

Some 70 fire engines from stations across London rush to Grenfell. But fire-fighters are severely restricted as they tackle this massive fire. The single stairway is very narrow. The tower lacks a sprinkler system.

Fire engines that do get close to the tower include ladders that can reach only 30 metres high. Sprayed water barely reaches the top floors of the 70-metre tower.

Grenfell lacks too a wet rising main. Only a dry rising main – where water is supplied by a fire engine – is extended and modified during the tower’s refurbishment in recent years.

Road access to the tower for emergency vehicles is hampered by the narrow local road network – and by the recent local addition of a large new building, the Kensington Aldridge Academy secondary school. The only way to and from the tower is through Grenfell Road, a narrow backstreet with car parked on either side.

Missing

It’s a breezy afternoon, a few days after the fire. The still smoking tower grotesquely blackens west London’s skyline. The looming sight of the tower stops people in their tracks as they try to inject some normality into their disrupted daily routines.

The grim tally of 72 dead still remains a long way off.

On the mixed income streets of Ladbroke Grove, less than mile from Grenfell, remnants of grief and desperation adorn walls, shop windows, doors, fences and gates.

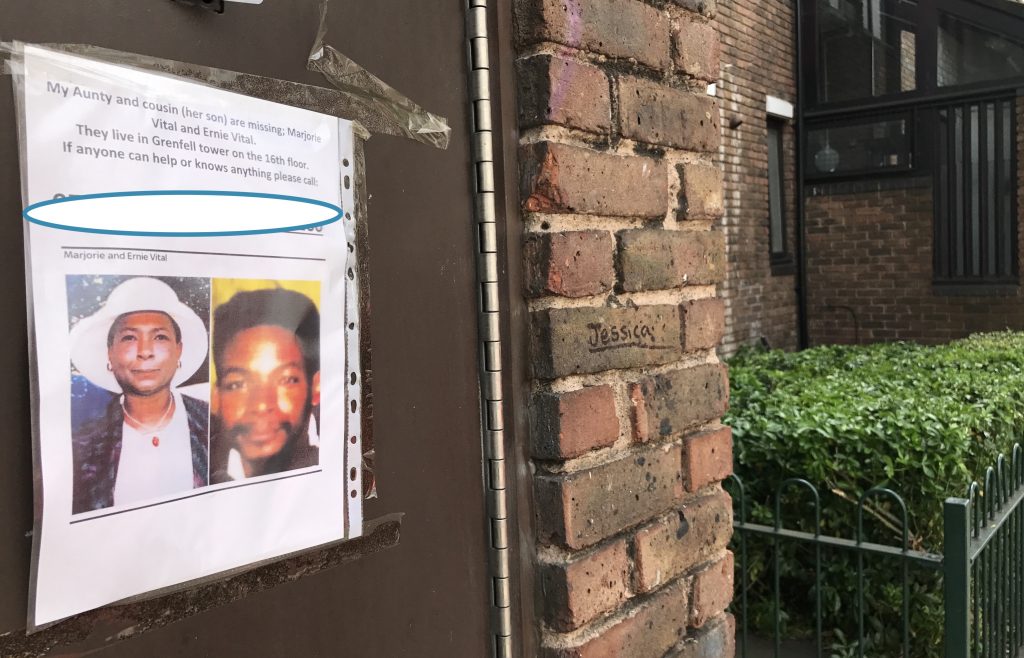

A sheet of A4 paper taped to a door bears a portrait photo of a dignified woman wearing a white hat alongside a close-up of a young man. The message states: ‘My Aunty and cousin are missing; Marjorie Vital and Ernie Vital. They live in Grenfell tower on the 16th floor. If anyone can help or knows anything please call.’

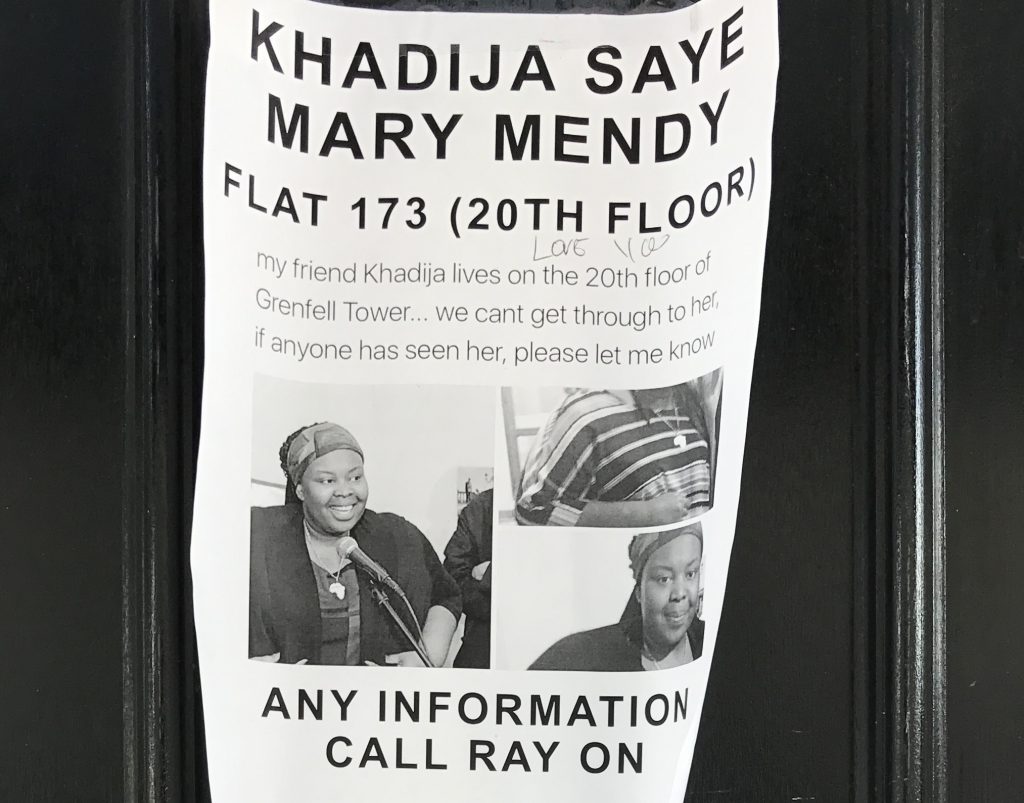

On a front door near Ladbroke Grove tube station, photos of Khadija Saye and her mother Mary Mendy adorn a notice that states: ‘My friend Khadija lives on the 20th floor…we can’t get through to her. If anyone has seen her, please let me know.’

A photograph of a child printed on a piece of paper is fixed to a hoarding next to the railway bridge that runs over Ladbroke Grove. The red bold lettering above the photo says: ‘MISSING: Have you seen Jessica Urbano? Missing from the Grenfell Tower. Approx 5ft with brown eyes and long curly hair.’

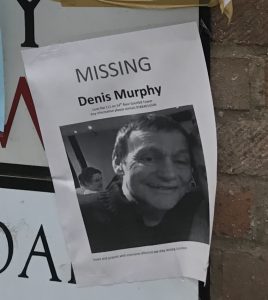

‘Missing: Denis Murphy. Lives on 14th Floor Grenfell Tower. Heart and prayers with everyone affected xxx stay strong London,’ states another flyer posted on a Wesley Square street sign.

‘Please help us find Nura, Hashim, Yahya, Firdaws & Yaqub’ states another notice with family photos.

Pinned to a railing on Maxilla Walk is a photo of a small dog on a leash. The caption reads: ‘This beautiful and much loved Chihuahua, Simba, managed to escape the Grenfell Tower fire with its owner but became lost in the aftermath. His 12 year old owner is recovering in hospital and is very much hoping to be reunited with him.’

Many people think hundreds of people must have perished in the fire. The police will only say the death toll will be high.

Lancaster West Estate

The Grenfell tower fire shakes the lives of people living in neighbouring blocks, estates and high-density residential streets. They are traumatised by the sight and sound of their relatives, friends and neighbours dying in the fire. A small army of volunteers with big hearts offer their humanity, compassion, sympathy and practical help to the survivors, bereaved and traumatised.

Completed in 1974, the 120 – then later 129 – flats in the Grenfell Tower form part of 900 homes on the Lancaster West Estate. There are six flats per floor.

The wider estate also consists of three long low-rise 5- and 6-storey blocks – Testerton, Hurstway and Barandon Walks, separated by grass landscaped areas and, until recently, by play areas for football and other games courts. The estate has provided publicly subsidised rented homes for generations of working class people. Some residents are leaseholders, having bought the homes they previously rented under Right to Buy.

Like most such council estates in London, the estate in its early years housed tenants grateful to be in good quality, clean and spacious homes in peaceful surroundings. The Grenfell Tower itself was built to mandatory Parker Morris Standards of space. Some 200 bedrooms were built; the tower has four 2-bedroom and two 1-bedroom flats on each floor. The first floor mezzanine includes a nursery. Dale Youth – an amateur boxing club – moved to the ground floor in 2000.

A central core houses the lift, staircase and vertical risers for the emergency services.

The local authority, the Royal London Borough of Kensington and Chelsea council, own the estate on behalf of local people.

But, in 1996, the Royal Borough transfers the management of its entire council housing stock – including Lancaster West Estate – to the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO). Established under the Conservative government’s Housing (Right to Manage) Regulations 1994, the KCTMO is described as ‘one of Britain’s most ambitious property management schemes’.

The KCTMO’s board at the time of the Grenfell Tower fire consists of eight local residents – drawn from across the borough – three members appointed by the council and two independents – although housing professionals effectively run the organisation in tandem with politicians who control it. This board now manages 9,459 Kensington and Chelsea properties of which 6,900 are occupied by former council tenants and 2,500 by people who, under Right to Buy, have bought leasehold the council flats they once rented. The KCTMO collects over £40 million in rent and around £10m in service charges each year.

The Lancaster West Estate – and the adjacent 700-home Silchester Estate - form a large part of the north-east corner of the Notting Dale electoral ward. Known also as Notting Barns, this neighbourhood is densely populated, ethnically mixed and predominantly working class.

Present

After the fire, survivors, bereaved relatives and Notting Dale residents walk their now unfamiliar streets in dazed shock. Trauma is etched on their faces. Many people pick up chunks of burnt insulation that lies all around the estates’ walkways and surrounding streets. Such material also lies strewn across the platforms of nearby Latimer Road, an above ground Hammersmith and City Line station on London’s tube network, now closed indefinitely in the wake of the fire.

An array of neighbourhood community organisations throw open their doors to act as ‘rest centres’ for traumatised and exhausted residents displaced by the fire; the Al Manaar Muslim Cultural Heritage Centre, Venture Centre, Canal Side, Harrow Club, Portobello Rugby Club, the Tabernacle Christian Centre, St Clement’s Church, and Queens Park Rangers Football Club.

The Lancaster Centre says it is open for ‘shelter, refreshments and support’. An emergency contact number at a ‘casualty bureau’ offers itself to anyone concerned about their loved ones. A small army of volunteers at ‘collection centres’ begin to receive and sort the vast plethora of donated clothing, toys, sanitary products, food and water that now pours into the area via an armada of vans.

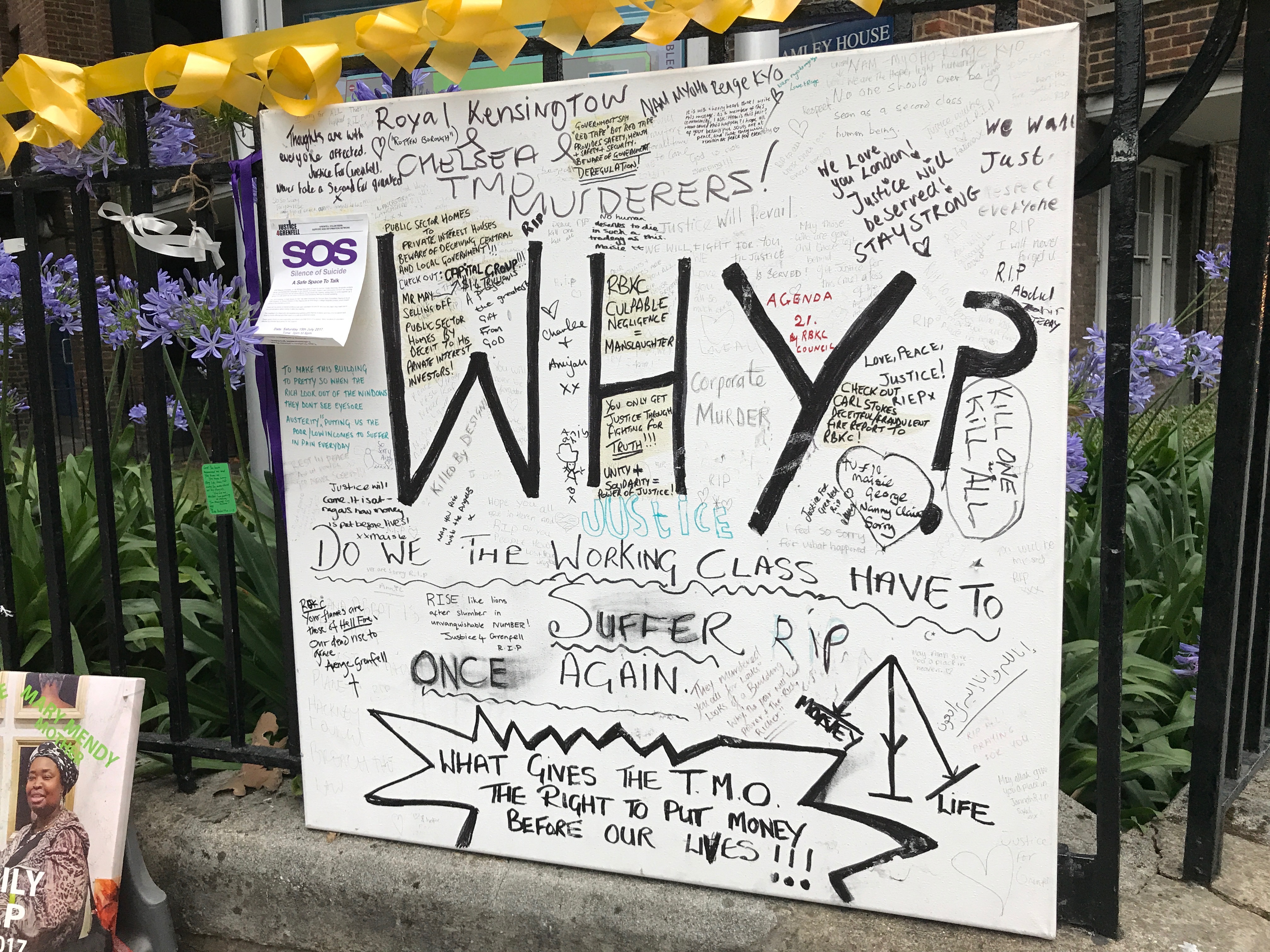

Immediately noticeable too alongside the presence of the community is the almost total absence of the local state. Elected politicians and appointed salaried officers of the local authority, the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, remain conspicuously absent, perhaps frightened by angry yet non-violent protests at the Kensington Town Hall.

In an entire afternoon, spent inhaling damp smoky air in the vicinity of the tower, I see only two officers wearing the council’s blue hi-visibility vests. They stand behind a table near the Westway Sports Centre quietly collecting the names and email addresses of people who wish to volunteer their help. All around them swirl an army of volunteers, people connected to local community groups, church organisations and the Red Cross, who are already helping impacted residents in a myriad of ways.

But when the people of an ethnically diverse working class local community need help the most, the local state is almost entirely absent. “We were abandoned by the state,” recalls survivor Eddie Daffarn. “It was the community which came and opened up the rugby club and St Clement’s and St James to give us sanctuary…only Grenfell residents could go into the rugby club. They protected us very well.”

Andrea Leadsom, the Leader of the House of Commons, visits the rugby club on the Friday morning after the fire. “We begged her to send people in authority to help us,” says Daffarn. “It wasn’t until the following Monday that the Westway Sports Centre put on facilities. Even then it was chaos.

“And we were in massive shock, dealing with our traumatic experience of losing our homes, the realisation we’ve escaped from a burning building, and our community’s members losing their lives.”

Identify

Forensic investigations to identify bodies and remains are painstakingly slow. Local people have no certain idea about just how many of their friends and neighbours – who used to walk these north Kensington streets – have perished.

Senior coroner Dr Fiona Wilcox is responsible for formally identifying victims. In the three weeks after the fire, Dr Wilcox formally identifies 21 people who have died and informs their families.

Police Commander Stuart Cundy says police have forensically transferred 87 visible remains recovered from the tower to the Westminster Mortuary. “I must stress that the catastrophic damage inside Grenfell Tower means that this is not 87 people,” says Cundy. “I cannot say how many people have now been recovered.”

Police speak to residents from 106 flats to ascertain who was in those flats at the time of the fire. Police say other people who were in those flats are dead or missing presumed dead. But, three weeks after the fire, police remain unable to trace or speak to anyone who lived in 23 flats spread from the 11th to the 23rd floor.

Detective Chief Superintendent Fiona McCormack, a homicide and counter-terrorism specialist, says police do not know for sure exactly how many people were in those 23 flats on that night. McCormack listens to 26 emergency 999 calls from people who said they were inside one of those 23 flats. Police assume no one from these flats has survived.

McCormack says international forensic specialists are involved with the Grenfell investigation. “But the tragic reality is that due to the intense heat of the fire there are some people who we may never identify,” says McCormack.

Survivors say that many tower residents were awake as they were eating to break their daytime fasts for the Islamic festival of Ramadan. The fire would have killed more people had they been asleep.

Nightmare

The grim process of forensic identification continues in the tower behind a strict police cordon. The tower is a crime scene. The Metropolitan Police starts a criminal investigation.

Just beyond this cordon, in the shadow of the now hideously disfigured Grenfell Tower, local churches – the Notting Hill Methodist Church, Latymer Community Church, St Clement’s Church and St Helen’s Church – are now hives of volunteers’ activity. They also act as places where residents vent their disbelief, grief and increasing anger to clusters of media.

Pauline, a local North Kensington resident, flicks through the pages of a book of condolence placed on a table outside Notting Hill Methodist Church. Pauline neatly and reverentially adds her own words to the book: ‘I can’t even imagine what you were all going through, watching it from my window I felt so helpless. Every single one of you are so courageous and for those that didn’t make it God truly bless your souls. RIP.’

A frail-looking elderly woman, a local resident, slumps to the pavement, overcome by the sight of dozens of ‘Missing’ notices, flowers and children’s crayoned drawings of a burning Grenfell Tower. Three women come to help her. She sits inconsolable. They sit with her on the paving stones and offer comfort.

A woman who lives on the Lancaster West Estate, wearing a cream hijab and light green tunic, pauses and stares at an ever-growing carpet of flowers on the steps outside the Methodist church. “Hundreds have died in the tower,” she says. “The authorities are lying to us, to stop us taking to the streets. They worry about riots.”

The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea, the local housing authority, owns the Grenfell Tower and is ultimately responsible for fire safety, including signing off as safe the tower’s recent building work and refurbishment. This refurbishment includes a form of exterior cladding.

However, a separate body, the Kensington and Chelsea Tenants Management Organisation manages the tower’s routine maintenance and commissioned contractors and materials for the tower’s refurbishment. The KCTMO chose a cheaper and flammable type of exterior cladding. Local residents immediately blame the cladding system for the fire’s rapid spread.

“I lost my friend in that fire,” says the woman with the cream hijab. “My daughter used to visit her friend there and sleep over. How can this happen in London, in this century?”

“I can’t believe my friends died there,” cries another woman. “I dream about this nightmare every night. We’re not going to let them get away with this.”

Pain, grief and sorrow

Relatives and friends of those ‘missing’ fear the worst but hope for the best. If the process of recovering bodies and remains is painstaking, formal identification and notification causes excruciating pain, grief and sorrow.

Denis Murphy, aged 56, earlier notified as ‘missing’, is identified as a Grenfell fatality ten weeks after the fire.

On that fearful night Murphy leaves his brother a voicemail at 01.30 saying: “I’m stuck in the fire. There’s black smoke everywhere and they are telling us to stay in the flat.” His last known contact is at 01:36. His phone then cuts out.

London-born Murphy, a devout Chelsea football fan, was ‘a fiercely proud Londoner but also proud of his Irish heritage’, according to his family who had moved from Limerick to the UK in the 1950s. The eldest of four children, a painter and decorator, Murphy had lived in North Kensington until aged eight. He had trials with Charlton Athletic and Crystal Palace football clubs.

Murphy met Tracy his wife in 1984 and they moved to Grenfell Tower. He moved back to the Grenfell Tower in 1997. His mother lives on nearby Portobello Road. He did voluntary work with adults with learning disabilities.

‘The pain, loss and sorrow we feel is indescribable,’ say the family. ‘To us Denis was an inspiration and an amazing, selfless, caring person…What really matters to us is what he stood for – family, friends, community, loyalty and love – and our lives will never be the same without him.”

Marjorie Vital, 68, lived on the 16th floor with her son, Ernie Vital, 50. Westminster Coroner’s Court is told Marjorie’s body is found on the 23rd floor along with that of Ernie – and at least 15 other victims. The two had migrated to London from Soufriere, the capital of Dominica, the West Indian island. Relatives say Marjorie, who worked in the textile industry for many years, was ‘a beautiful, joyful, independent, intelligent, kind-hearted, sensitive individual, who dedicated her life to her children…Through her creativity and joy of life she was an inspiration to us.’

The family pay tribute to Ernie as ‘a creative individual, a proud, humble, mature and independent man…who will be remembered as kind, sensitive and caring person with a warm-hearted smile’.

Dental records help to formally identify Mary Mendy, 52, as a victim of the fire. Although Mary, also known as Cissy, lived on Grenfell’s 20th floor with her daughter, she is found on the 13th floor. Mendy’s brother, Nathaniel Johnson, says Mary, originally from Gambia, was a ‘shining light’. Her sister Betty Jackson, says on behalf of the family: ‘My beloved sister, words can never describe the pain of losing you. I can’t believe you are gone. You were a wonderful sister, an incredible aunt, the best mother any child could have wished for. You were an amazing friend to all those who knew you…You will remain forever in our hearts, you and your beautiful daughter Khadija’.

Khadija Saye, 24, is found on the 9th floor and is identified via dental records. Also known as Ya-Haddy Sisi Saye, Khadija is a photographer and artist, much of her work based on Gambian spiritual practices. Her work is being shown in the Venice Biennale arts festival – her career is flourishing at the time of her death. A memorial fund is launched in Khadija’s name to fund opportunities for new young artists.

The Grenfell children

The Grenfell fire also kills 18 children of all ages. All life is precious, or ought to be so – and all of the people who lost their lives in the Grenfell fire represent a terrible loss. Children, though, are supposedly revered in 21st Century London culture. Gone is the systemic child labour and grinding poverty of Victorian London. Children command society’s protection through evolving welfare codes of conduct and law. Child abuse, though still all too frequent, is scandalised, investigated and its exponents vilified and punished.

Children, so these codes say, should never be scared, threatened or abused let alone maimed or killed, through either carelessness or wilful neglect. Yet the rapacious spread of the Grenfell fire obliterates these societal child protection codes as if they never existed. Fire safety regulations are not informed by residents let alone led by them. Yet residents and their children are those who bear the utmost risk.

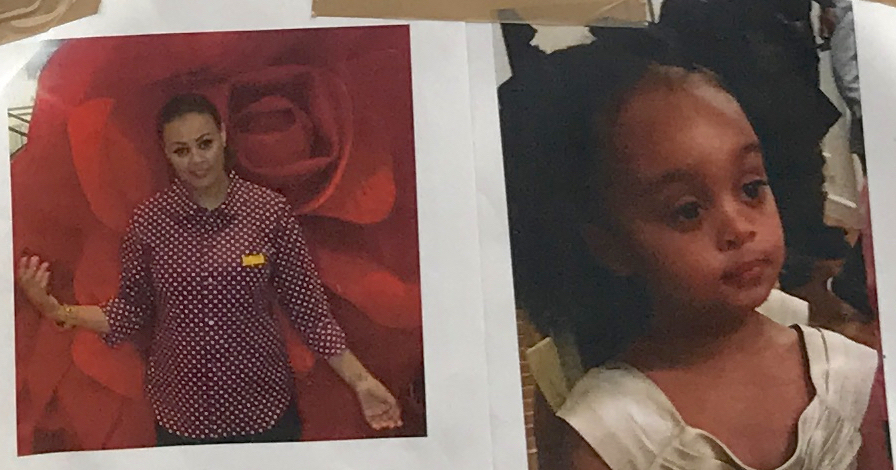

Hence, the quiet, privately taken family photos of children who later die in Grenfell now loudly and publicly speak of an unbearable loss. The Metropolitan Police says some of the families of the 71 victims, formally identified by coroner Dr Fiona Wilcox, have agreed to their lost ones being named. Named child victims include:

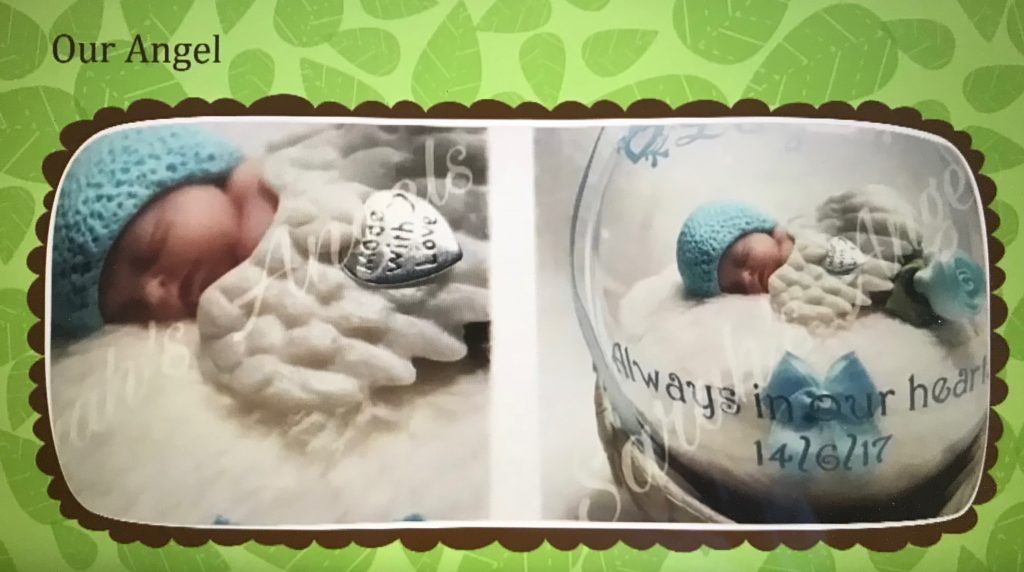

Logan Gomes, (below image) who police record as a victim of the fire after he is stillborn on 14 June. Logan was due to be born on 21 August. Both parents Marcio Gomes and Andreia Gomes – and their daughters, Luana and Megan, survived the fire. They lived on the 21st floor and escaped around 04:00. They describe Logan as “our sleeping angel”.

Leena Belkadi, aged six months, is found dead in her mother’s arms on a stairwell outside their 20th floor flat. Firefighters recover Leena’s sister, Malak Belkadi, aged 8, but she dies later in St Mary’s Hospital. Sister Tazmin Belkadi, 6, also taken to hospital, survives. Both father Omar Belkadi and mother Farah Hamdan, are found dead on the stairwell.

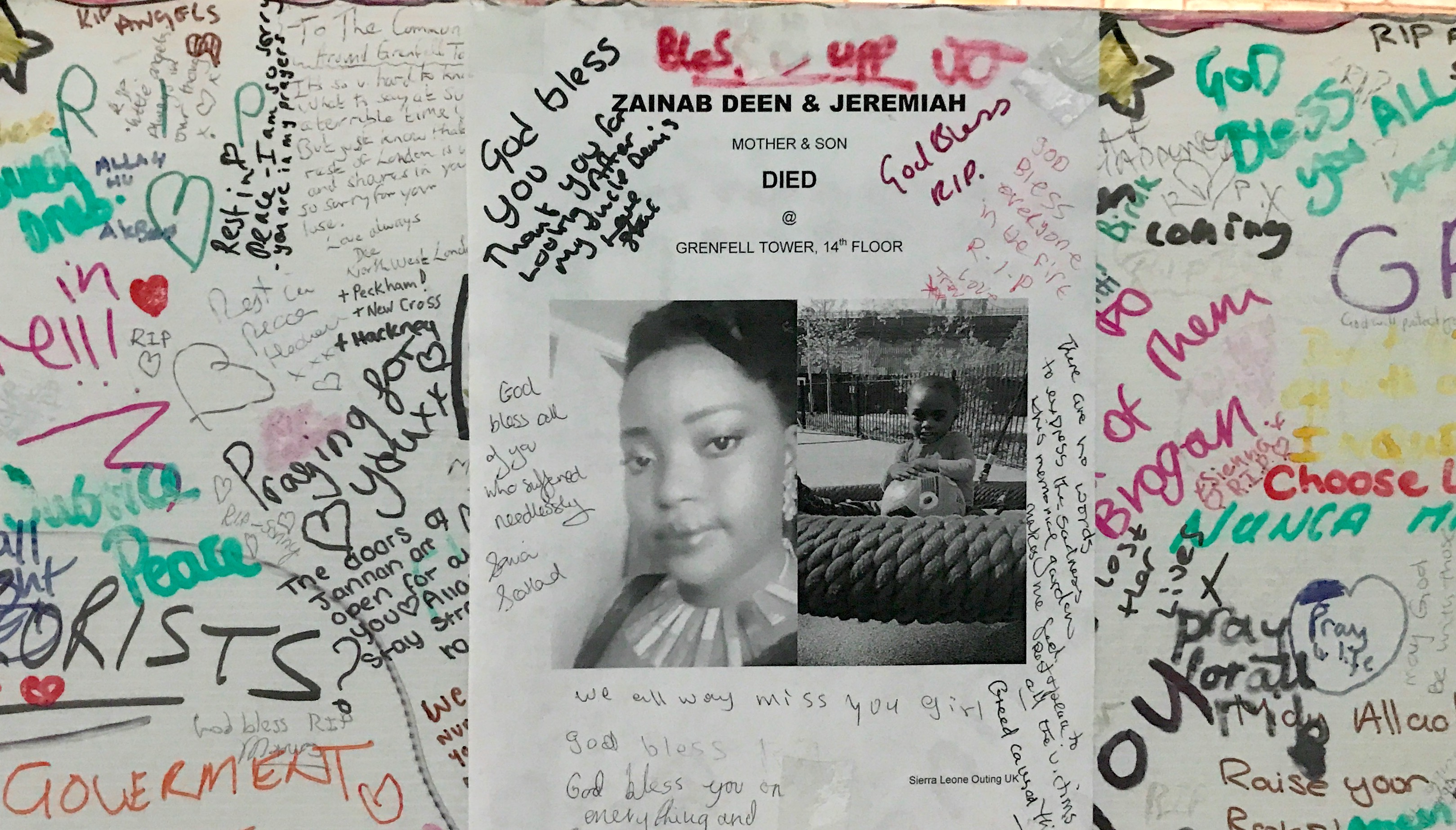

Jeremiah Deen, aged just two, dies with his mother Zainab Deen, 32, after being trapped on the 14th floor. The Metropolitan Police confirm Jeremiah’s death in August 2017. “He was a playful, innocent young boy whose life never got the chance to start,” says father and grandfather Zainu Deen. “Zainab was a good mother and would have done anything she could to keep Jeremiah safe.”

Remains of Amaya Tuccu-Ahmedin, aged three, are found in the 23rd floor lobby, next to her mother, Amal Ahmedin, 24. The body of Amaya’s grandfather, Mohamednur Tuccu, 44, is recovered from close to an adjacent leisure centre. The trio are thought to have visited Amna Mahmud Idris, 27, Amal’s cousin, who also dies.

Hania Hassan, aged three, and sister Fethia Hassan, four, dies along with their mother Rania Ibrahim, 31. Ibrahim is last heard sending a video from inside Grenfell.

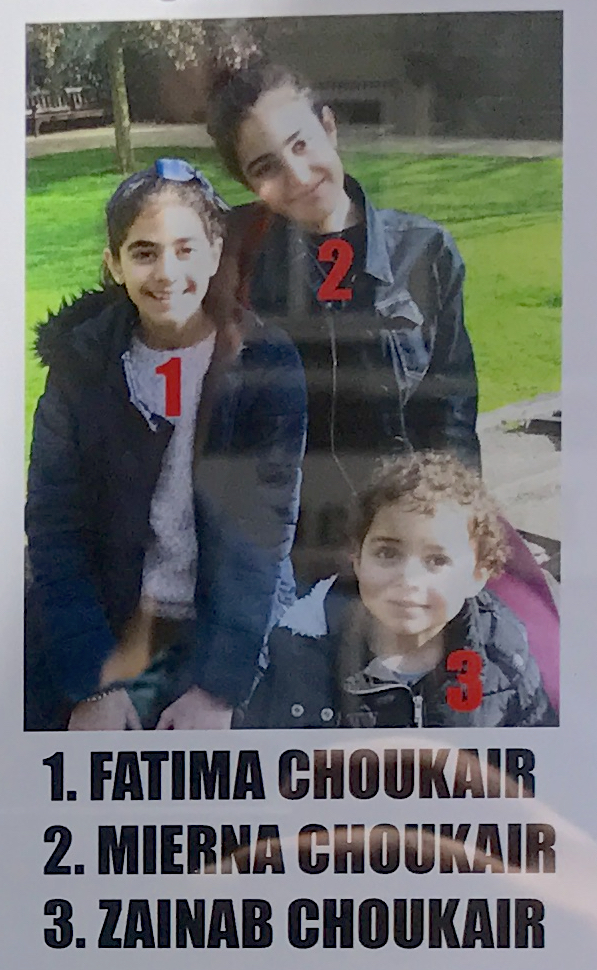

Zainab Choukair, three, is one of six members of the same family, who live on the 22nd floor. A Westminster coroner confirms at an inquest Zainab died in the fire with Fatima, 10, and Mierna, 13. They die along with their parents, Nadia Choucair, 33, and Bassem Choukhair, and grandmother Sirria.

Issac Paulos, aged 5, is a pupil at Saint Francis of Assisi primary school, who lived with his Ethiopian parents Genet Shawo and Paulos Petakle, and three-year-old brother, Luca, on the 18th floor. His mother wraps Issac’s head in a wet towel but he loses hold of his neighbour’s hand as they try to escape. Issac’s body is later found on the 13th floor, identified from dental records. ‘We will miss our kind, energetic, generous little boy,’ says Issac’s family. ‘We will miss him forever.’

Yaqub Hashim, six, Firdows Hashim, 12, and Yahya Hashim, 13, formally identified as victims, die along with Hashim Kedir, 44, and Nura Jemal, 35.

Yahya was a kind, polite and loving boy. He attended Kensington Aldridge Academy. He read the Koran and always prayed five times a day. He was a keen footballer. Yahya’s aunt describes her nephew as ‘the most kind, polite, loving, generous, thankful and pure hearted boy…you used to laugh so much…I miss that laugh so much’.

Firdows is described as beautiful, intelligent and eloquent. She attended Avondale Primary School and Kensington Aldridge Academy. She loved to read and borrowed and finished five books each week from the library. Her family say Firdows is the ‘most intelligent, wise and eloquent girl…so smart and mature for your age that everybody had a lot to say about the type of future you were going to have; the future that was stolen from you’. Firdows had a “beautiful voice” and she won a national debating contest.

Avondale School friends describe energetic and sharp-minded Yaqub as a ‘funny hilarious honey with a big smile, a great boy and a kind friend’. Yaqub was born in the Grenfell Tower in 2011. “His very presence was a spark of happiness,” say his family.

The children liked to visit their cousins in Norway – and receive them in London in turn.

Mehdi El-Wahabi, aged eight, is also formally identified. Mehdi died with Nur Huda El-Wahabi, his 15-year-old sister. They die with their older brother, Yasin, 20, and their parents, husband and wife Abdulaziz, 52, and Faouzia El Wahabi. ‘Mehdi was a calm and friendly young boy who loved his family very much,’ says his family. ‘He was loved by staff and pupils at his school who held a beautiful memorial and made a plaque in memory of him.’ Mehdi’s cousin Senate Jones adds: ‘You made me laugh and smile every day.’

‘Nur Huda was lovable, smart and kind person,’ says her family. ‘She had a lot of potential and that can be recognised in her recent GCSE exam results. We are proud of her and will continue remembering her and all our family and friends who have died in this tragedy.’

Biruk Haftom, 12, also dies in the fire along with his mother, Berkti Haftom, 29. ‘Biruk was a loving, pure hearted boy, wise beyond his years and known for his politeness, kind heart and his love for his family and friends. Berkti and Biruk left an everlasting legacy full of lovely memories and their contagious laughter and charisma will live in our hearts forever. We are deeply hurt and heartbroken our angels were taken from us so cruelly, so young. We will not rest until justice is served.’

At the end of July 2017, Jessica Urbano Ramirez, aged 12, is also formally identified as a Grenfell victim. Jessica, of Latino origin from Colombia, is one of those described on the flyers as missing. Jessica’s school friends say: “Jessica was bubbly, proud of her Latino roots, and would talk to everyone”. They still send text messages to her.

Jessica’s parents say: ‘Over the past weeks we have been in a state of confusion and limbo. Now that she has been formally identified we feel totally crushed. Our little girl was loving, kind hearted and caring. She brought joy to everyone who met her and her laugh was contagious…Her light will shine bright and will light our individual paths…’

Before the fire

Ramirez’s parents show their anger too. ‘Nothing will ever bring our little girl back, and we are angry that this should ever have happened to our little angel. We will not rest until we get justice for her and for the many other lives lost as a result of this crime. We will only f

eel justice has been served when the highest possible charges are applied to culpable individuals. We entrust this task to the authorities in the hope that we will not be let down.’

Some local residents believe the authorities have already jettisoned the local community. For instance, people like Joe Delaney, who lives on the Lancaster West Estate. Residents believe the Grenfell Tower fire is the almost inevitable outcome of the RKBC and the KCTMO’s ‘malign’ matrix of ‘ineptitude, incompetence and institutional indifference’.

Joe Delaney saw two people fall from Grenfell Tower. Delaney lives in a Lancaster West Estate block next to the tower. He says the management company and councillors and council officers were “warned before, during and after the regeneration” about Grenfell’s lack of fire safety.

Grenfell Action Group

This warning is not cut-rate recollection that supports some cheap hindsight. Survivor Eddie Daffarn says the Grenfell Action Group, styled as ‘working to defend and serve the Lancaster West Estate community’, published blog postings for at least five years warning about fire hazards at the tower.

Most notably, in November 2016, seven months before the fire, the blog posts a frightening prophecy: ‘It is a truly terrifying thought but the Grenfell Action Group firmly believe that only a catastrophic event will expose the ineptitude and incompetence of our landlords, the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation, and bring an end to the dangerous living conditions and neglect of health and safety legislation that they inflict upon their tenants and leaseholders…

‘Unfortunately, the Grenfell Action Group have reached the conclusion that only an incident that results in serious loss of life of KCTMO residents will allow the external scrutiny to occur that will shine a light on the practices that characterise the malign governance of this non-functioning organisation.’ (Grenfell Action Group, 20 November 2016).

It is extremely rare for such a truly terrifying event to be so prophetically forewarned. The GAG says the authorities wrote to them threatening legal action rather than heed those warnings.

Access

Almost three years before the fire – in August 2014 – Grenfell residents wrote to the London Fire Brigade of their concern that ‘the new improvement works to Grenfell Tower have turned our building into a fire trap’. In their letter, the residents state: ‘There is only entry and exit to the tower block itself and, in the event of a fire, the LFB could only gain access to the entrance to the building by climbing four flights of narrow stairs.’

Even with clear access, only one fire engine can stand at the base of the tower. Residents tell the London Fire Brigade: ‘There should be no parking at any time in this area except for emergency vehicles only. Indeed, there is barely adequate room to manoeuvre for fire engines responding to emergency calls, and any obstruction of this emergency access zone could have lethal consequences in the event of a serious fire or similar emergency in Grenfell Tower or the adjacent blocks.

‘Knowingly compromising this essential emergency access…would be highly dangerous, criminally negligent, and could prove lethal in the event of a serious fire emergency – which could occur at any time.’

Putting lives at risk

In May 2013, residents also tell the council and the TMO about continuous electrical power surges that led to appliances, such as computers, burning out and even catching fire. They feel nothing was done to properly investigate and remedy these power surges and subsequent loss of water supply.

Later, it will also emerge, the London Fire Brigade had issued an audit tool in 2015 to prompt and help all 33 of London’s local authorities to carry out fire risk assessment on refurbished high-rise blocks. The worry was cost concerns had led to refurbished estates being signed off without proper assessment.

The Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea – that owns the Grenfell Tower and which is ultimately responsible for the safety of its residents – would have received one. But only two such London councils – Enfield and Kingston upon Thames – apply the audit.

Fire, race and class

The GAG’s warnings, amplified by Daffarn, now fuel race and class accusations about the Grenfell fire. This perspective says no London residential tower of penthouses and suites – and no town hall and certainly not the Houses of Parliament – would be at such fire risk from flammable cladding as that which covered the Grenfell Tower.

No London glass and steel corporation or bank HQ faces such peril from power surges. All such buildings are likely to be furnished with sprinklers, wet risers, central fire and smoke alarms and good access for emergency vehicles.

Worse still, according to this narrative, in 2012 politicians in Parliament tried to serve corporate interests by deregulating fire safety acts across England that they regarded as mere ‘red tape’, as procedural and financial burdens on the construction industry. Fire inspectors also say an overly complex hierarchy of command has dithered and then done nothing about their recommendations for council housing blocks and towers.

This deregulation and dithering has continued unabated despite recommendations to strengthen fire safety following inquiries into the deaths of six women and children at the Lakanal House fire in July 2009 and the loss of firefighters James Shears and Alan Bannon at the Shirley Towers blaze in Southampton in April 2010.

“Fire safety became a concern for us early on,” recalls Daffarn. “It appeared to be a dereliction of duty on behalf of our landlord (the KCTMO). We had no confidence in their ability to keep us safe. Their concern was to look after themselves.

“Our (the GAG) blog is on record as describing the TMO as a ‘mini-mafia, a non-functioning organisation. It felt like we were a carcass and they were the vultures feeding off us.”

Class and countries

Fire itself, of course, is no bigot. Fire kills and maims indiscriminately, like any natural force such as an avalanche, earthquake, hurricane or a tsunami. But this is not a natural disaster.

The 72 Grenfell fire victims and their families are working class. They include taxi drivers, teachers, cleaners, architects, a café waitress, a shopkeeper, a public relations officer, a hairdresser, an army officer, and an artist receiving early international recognition.

Those killed originate from 18 different countries; 33 people from Britain, and others from Morocco, Eritrea, Egypt, Iran, Sudan, Lebanon, Afghanistan, Italy, Bangladesh, Ethiopia, India, Sierra Leone, Ireland, Syria, Gambia, Dominica, Philippines. Reportedly more than half of the adult victims had come to Britain since 1990; some as refugees from strife-torn countries. Others are long-term migrants to Britain who came decades ago and have spent their lives working in London and raising their families.

For instance, four of Grenfell’s victims and several of its bereaved residents and survivors are of Moroccan origin. Some local residents call part of Grenfell ‘the Moroccan flats’. Of the estimated 60,000 Moroccans in the UK, 35,000 live in London, with the largest community being some 8,000 people living in North Kensington. Some famously serve tagine and mint tea to locals and visitors on the Golborne Road, near Portobello Road market. Many Sunni Muslims of Moroccan origin pray inside the Golborne Road and Al Manaar mosques.

In the fire’s horrid immediate aftermath, survivors also report they have lost cash but also important documents that establish identity, citizenship and rights to services and benefits. These include passports, naturalisation and visa certificates, driving licenses, national health and national insurance numbers, college and university degrees and utility bills. The Home Office says it will not use this ‘tragic incident as a reason to carry out immigration checks on those providing vital information to identify victims’.

Three acts

“The fire is a three act tragedy,” says Daffarn. “The first act was pre-Grenfell; how we were treated as a community. How such an eloquent, ethnically, socially and economically diverse community could be treated – bullied, ignored, marginalised, not listened to, in the 21st century, in the fifth richest country in the world.

“The second act of the tragedy is what happened on that evening in the aftermath, and how we were just abandoned and left by the state. And how it was the community that came and rescued us.

“The third act is everything subsequent to that – how eleven months after the tragedy many homeless families – many with children – are still living in hotels.”

Public Inquiry

The Metropolitan Police states its criminal investigation into the Grenfell Tower fire represents ‘one of the largest and most complex in the Met’s 188-year history’.

Prime Minister Theresa announces the day after the Grenfell fire that a public inquiry will be held. The Queen, in her speech to Parliament one week later, says: “My government will initiate a full public inquiry into the tragic fire at Grenfell Tower to ascertain the causes, and ensure that that appropriate lessons are learnt.”

The inquiry will be headed by Sir Martin Moore-Bick, a retired judge, and will include other panel members more likely to represent the concerns raised by Grenfell’s survivors, bereaved families and residents. Moore-Bick describes the fire as “an event of unimaginable horror”. Later, Moore-Bick states: “The truth must be laid bare to ensure justice for the living and a tribute to the dead.”

Phase one of the inquiry commemorates those killed. The second longer phase will examine who took the decisions as to why the tower was refurbished in this way.

Hackitt review

In July 2017, the government also announces a review of building regulations and fire safety led by Dame Judith Hackitt. People on the streets of Notting Dale – and those in public and private residential buildings clad with flammable cladding – demand to know if the review of building regulations and fire safety will result in greater fire safety for tower blocks. Some people live in gleaming modern 21st Century-built residential towers with cladding that now renders them unsafe. Fire safety officers patrol these developments with megaphones in case of fire.

In May 2018, Hackitt’s final report is published amidst confusion. Hackitt fails to recommend a ban on combustible cladding on residential buildings – even though she says the construction industry in Britain operates a broken system that needs to be fixed.

Hours after the report’s publication, the government says it will consult on outlawing such flammable building materials.

“I’ve found problems with the building of high rise buildings that goes far beyond people putting cladding on to them which is not compliant,” says Hackitt.

Regeneration history

Hackitt’s failure to recommend a ban on combustible cladding on residential buildings is roundly criticised. But her comments on deeper problems find an echo in the recent ‘regeneration’ history of the Grenfell Tower.

But do the strands of this ‘regeneration’ history pull together? Are they threads that lead to the fire?

Further investigation is needed but the following potted history ought to be worthy of more detailed exploration. Around 2007, politicians at the Royal Borough of Kensington began to actively pursue an ambition to ‘regenerate’ the Lancaster West Estate, Silchester Estate and some of the surrounding Notting Dale area. They chiefly sought to achieve this regeneration via ‘selective demolition’ and redevelopment of the estates. As a commissioned Urban Initiatives Studio report of 2009 stated, the aim was ‘to create a more successful urban neighbourhood through selective demolition of existing housing stock and the reprovision of high quality new homes for both affordable and private tenures’.

Regeneration could ‘deliver significant returns to the council’, mainly through increased council tax revenues paid by an influx of new wealthier residents displacing existing residents on average and lower incomes.

Visual appearance

The report speaks of ‘how sensitive the potential residual land values are to residential sale values and, in particular, to the potential values for high-end flats and houses. To achieve the highest values, the area will need to undergo significant change to improve its visual appearance’.

The same report say the Grenfell Tower is deemed a building that ‘blights much of the area east of Latimer Road Station…On balance our preferred approach is demolition.’

The council did accept such a regeneration would break up the existing and long-established ethnically diverse working class community in Notting Dale. Perhaps though, they sought comfort in the regeneration justification mantra; ‘regeneration is just like making an omelette, a few eggs must be broken’.

Fire crew access

However, the banking crisis, global financial meltdown and recession over 2007-10 seem to have indefinitely quashed this regeneration ambition. Instead, the Royal Borough approved the building of the Kensington Aldridge Academy, a non-selective secondary school for local students, funded directly by the government and sponsored by Aldridge Education, a ‘national multi-academy trust’.

The Academy welcomed its first year cohort in September 2014 and was opened by the Duchess of Cambridge in January 2015. “This is a landmark day for the North Kensington community and represents our ongoing commitment to investing in great facilities for our residents,” says then council leader, Sir Merrick Cockell.

Built by Bouygues UK, the £28 million Academy, welcomed by some in the wider community, faced concerted opposition from Grenfell Tower and Lancaster West Estate residents during the planning process. Residents protested it took land away from the estate that contained much-used sports pitches. – and, albeit now with 20-20 hindsight, that it reduced the access of fire engines and ambulances to the tower.

In June 2017, days after the fire, Daffarn reminds Royal Borough councillors of residents’ opposition to the Academy proposal at an extraordinary council meeting. Hundreds of protestors, angered at council’s role in the fire, cannot get into the council chamber and watch Daffarn speak via a large screen rigged up in the town hall’s square.

“We wrote to you in July 2010 on the eve of your cabinet taking the decision to fund the Kensington Aldridge Academy,” Daffarn forthrightly tells the newly appointed Royal Borough council leader Elizabeth Campbell. “We told you that if you build this Academy you will be putting the fire safety of Grenfell Tower residents at risk. And you ignored us. The way you treated our community groups was despicable.”

The school opened with its first pupil cohort in 2014 and the Duchess of Cambridge attended its official opening in January 2015.

A lethal refurbishment

How and why exactly did the refurbishment of the Grenfell Tower – as opposed to its demolition and the regeneration of the wider Lancaster West Estate – emerge from this scenario? Was the tower’s refurbishment an attempt to appease Grenfell Tower residents opposed to the loss of their local amenities caused by the newly adjacent Academy?

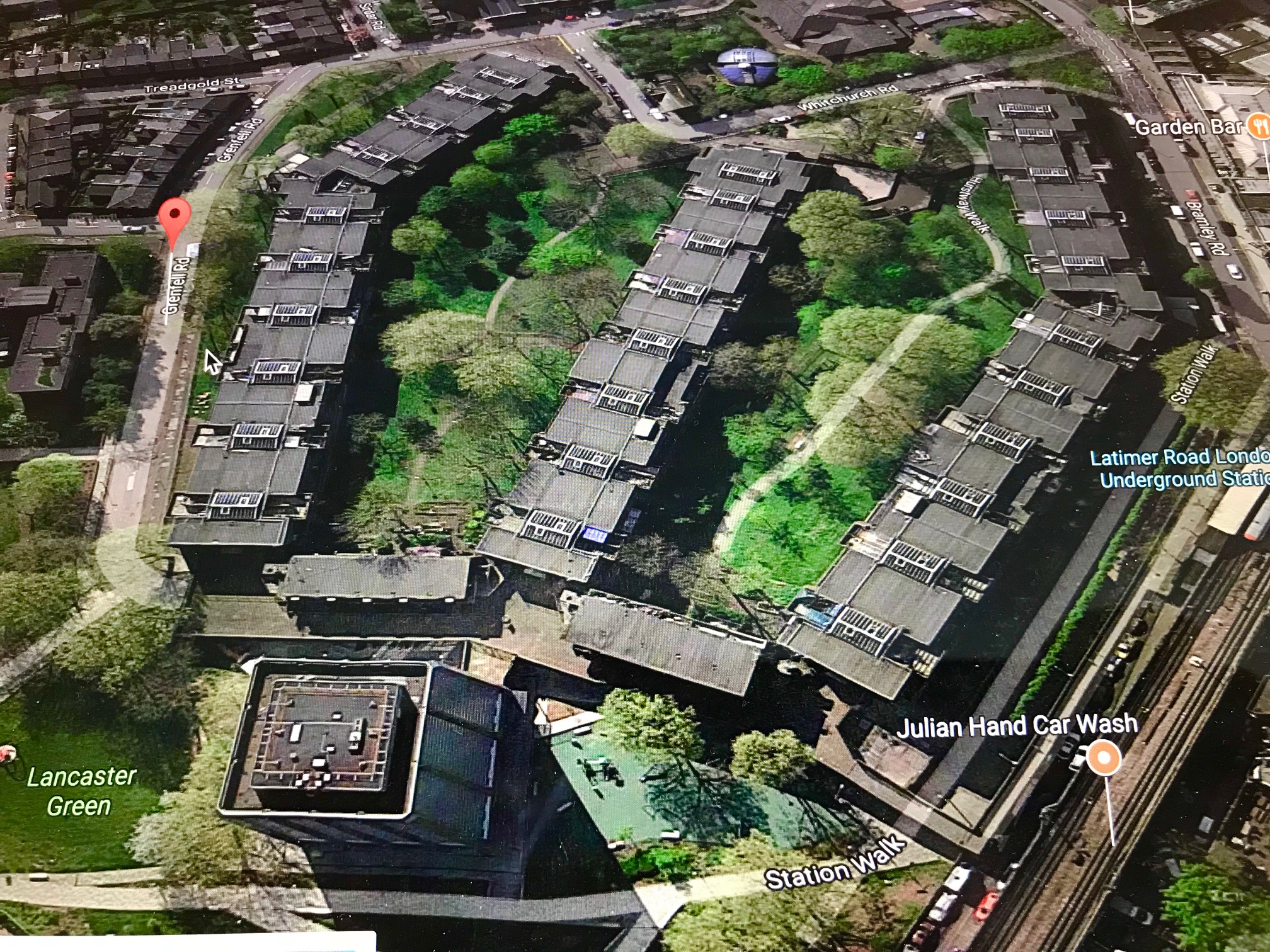

The purpose of the cladding fixed to the Grenfell Tower was understood initially as a ‘rainscreen’ to protect the tower’s original concrete exterior and to provide the building with greater ‘thermal efficiency’. A Google Map view of Grenfell Tower of October 2015 from the nearby Westway road shows cladding being applied to the north-western corner of the block (see below).

But some local residents also suspect the refurbishment was intended as a way of improving the tower’s external appearance so as to make the area more attractive to future potential developers and real estate investors. They point out that the ambition to regenerate the Silchester Estate remained alive before the Grenfell Tower fire snuffed it out.

Freedom to see information

Would an attempt to ‘cosmetically’ improve the outward appearance of the Grenfell Tower provide any understanding of a later decision to refurbish the block with a cheaper flammable cladding system – a refurbishment that would be lethal and fatal?

Eddie Daffarn says the GAG submitted Freedom of Information Act requests to find out about the refurbishment but the requests to see documents went unanswered. The TMO was not legally obliged to answer them. “Had we access to those documents we would have seen the changes in the cladding,” says Daffarn. “We originally intending to use non-flammable cladding. They then changed to using flammable cladding. Had we access to those documents I believe we would have been able to challenge those changes.”

Daffarn says the GAG requested but was denied access to documents on meetings between the KCTMO, the council, the refurbishment contractor Rydon and architects Studio E. “It is vitally important the laws are changed so legislation allows anyone who lives in social housing to have access to that kind of information,” says Daffarn.

Goldmine

It’s too early to say, at this stage, that 21st Century London’s ‘brave new world’ of council estate regeneration guided those in power to the false logic of a cheaper and cosmetic refurbishment of this tower block.

Eddie Daffarn has lived for 16 years on the estate. His comments in May 2018 about the Royal Borough point in the direction of the landlord TMO’s contempt for its tenants and to the council’s ambitions to ‘regenerate’ – or privatise – the estate and the wider neighbourhood. As in other London neighbourhoods targeted for such real estate driven ‘regeneration’, an ethnically diverse working class community seems to have been deemed by local politicians as not worth they land that they live on.

“It was obvious to us that our local authority was not interested in keeping us safe, was not interested in scrutinising the individuals who were responsible for keeping us safe. Their interest was in regeneration,” says Daffarn. “They understood we lived in North Kensington on a goldmine. They didn’t have to dig for this gold. They simply had to marginalise the people who were living there, push us to one side, change the mixture of people living there, build new accommodation for property development, private education.

“The council had a third of a billion pounds in reserves – yet they were cutting £100 off their council tax for people who were not on benefits. Money was not the issue. There was something more sinister at play. It was a class act driven by greed and by their understanding of the value of the land that we lived on.

“Yet I don’t think it is helpful to dress it in just class politics because there were real individuals who we know – who hopefully will face justice and criminal prosecution – who will have to explain their actions to Sir Martin Moore-Bick in front of the nation – and they will have to explain why they acted in the way they acted.”

Lakanal House

Daffarn is less confident about Moore-Bick’s readiness to delve deep into the ‘cultural’ elements of the council and the TMO’s behaviour. Moore-Bick spoke with residents one week after Prime Minister Theresa May appointed him to lead the public inquiry. “He informed us he didn’t have confidence in himself to look at the cultural issues,” says Daffarn. “Like, what motivated the council, why they didn’t scrutinise the KCTMO, and what were these drivers of regeneration for handing over these public assets to private property developers and private education. These are the questions we need him to look at.

“It is too early to say whether the truth will come out of the inquiry. The inquiry needs to come up with findings that will be implemented by government. If the findings that came out of the inquests into the Lakanal House fire in 2009 had been acted upon, then Grenfell would never have happened.”

So, post-Lakanal House, what were the council and TMO doing? Daffarn says the Royal Borough of Kensington and Chelsea’s key councillors and lead officers “spent their time sweating the assets of North Kensington, our library, information centre and community centre. Their focus was on that, not on keeping us safe. A consequence of this was Grenfell happening. If the council and the TMO had treated us with a modicum of respect and humanity, Grenfell would have been avoided.”

Treated properly

Daffarn sees a way forward. That direction needs to reach the full revelation of the whole truth about how, what and why Grenfell happened. It needs to unearth who knew what and when before the heartbreaking catastrophe took place. It must reach a destination of justice where those who were responsible – especially for the cheaper flammable cladding decision – are brought to justice, along with those who failed in their duty to scrutinise such decisions and people.

The longer-term way forward, says Daffarn, must also involve an even more profound change. “We need to change the culture around social housing,” he says. “Our community has been painted as work shy, immigrants, sub-letting. That could not be further away from the truth. We are eloquent, hard-working and long-term residents.

“We did not deserve to be treated the way we were treated.

“Every community in social housing needs to be treated properly.”

The Grenfell Tower Inquiry began on Monday, 21 May 2018.

© Paul Coleman, London Intelligence ®, 2018. All Rights Reserved.